The winter of 5702 brutalized the Jews of the Warsaw ghetto with unforgiving cold. Chaim Kaplan, a school principal whose journal Scroll of Agony survived the war, recounts in his typically blunt prose how the physical privations of January 1942 affected the spiritual life of Ghetto inhabitants:

Gone is the spirit of Jewish brotherhood. The words “compassionate, modest, charitable” no longer apply to us. The ghetto beggars who stretch out their hands to us with the plea, “Jewish hearts, have pity!” realize that the once tender hearts have become like rocks. Our tragedy is the senselessness of it all. Our suffering is inflicted on us because we are Jews, while the real meaning of Jewishness has disappeared from our lives.

Our oppressors herded us into the ghetto, hoping to subdue us into obedient animals. Instead, however, we are splitting and crumbling into hostile, quarrelsome groups. It is painful to admit that ever since we were driven into the ghetto our collective moral standard has declined sharply. Instead of uniting and bringing us closer, our suffering has led to strife and contention between brothers. The Nazis, possibly with malice aforethought, put us in the hands of the Judenrat so that we might be disgraced in the sight of all. It is as if they were saying, “Look at them! Do you call them a people? Is this your social morality? Are these your leaders?”

It is not at all uncommon on a cold winter morning to see bodies of those who have died on the sidewalks of cold and starvation during the night. Many God-fearing, pious souls who, if the day happens to be the Sabbath, are carrying their tallith under their arms, walk by the corpses and no one seems moved by the sight. Everyone hastens on his way praying silently that his will not be a similar fate. In the gutters, amidst the refuse, one can see almost naked children who were orphaned when both parents died earlier in their wanderings or in the typhus epidemic. Yet there is no institution that will take them in and care for them and bring them up as human beings. Every morning you will see their little bodies frozen to death in the ghetto streets. It has become a customary sight. Self-preservation has hardened our hearts and made us indifferent to the suffering of others. Our moral standards are thoroughly corrupted. Everyone steals! Petty thievery, such as picking pockets or stealing a hat or umbrella, is common. Because kosher meat is terribly expensive, people have relaxed their observance of the laws regarding the eating of kosher food. Not only atheists and derelicts are guilty of this, but synagogue sextons and pious men as well.

It is Nazism that has forced Polish Jewry to degrade itself thus. Nazism has maimed the soul even more than the body!

The Piaseczno Rebbe’s words on the Shabbat of Parashat Shemot responded to the moral decline of the beleaguered Jewish population. The Rebbe was certainly aware of the ethical challenges of life in extremis in the Warsaw Ghetto. He identified three types of people who fear sin, for different reasons:

There is a kind of person who understands the bitterness of punishment for each and every sin, Heaven help us. There also exists a greater type of person for whom the concept of sinning against God is in itself egregious. This is without reference to a specific sin, rather it refers to anything which is contrary to God’s will, nonetheless he is not conscious of any personal sin, and he feels no fear that he may yet sin, continually assuring himself that he is good and his actions are good. There is a third type of person, however, who is continuously in a state of trepidation that he not sin, and his heart is broken within him, saying ‘who knows if even now I am not rebelling against God?’ Insofar as he is sensitive, and always fearful, then he always discovers his own shortcomings.

The difference between the three is as follows: the first one, even though he knows the enormity of a given sin, has nevertheless failed to internalize fear within himself, and his heart does not tremble that he not sin. The last of the three has internalized fear of sin, and his body, mind, and heart have been sensitized and tremble, that he not sin, finding within himself his shortcomings, and out of this extreme concern, he repents and those shortcomings are not able to take root within him. Since the fear of sin and thoughts of repentance were established within himself prior to an act of sin, consequently repentance comes speedily after any shortcoming, Heaven forbid.

The last category—the person who feels deep concern for sin, even without committing any transgression—is discussed extensively in the Rebbe’s prewar writings, and is considered one who is capable of experiencing tremendous joy and spiritual growth. In the context of fear of sin, the Rebbe explains that this is because fear is an emanation fro the kabbalistic sefirah known as gevurah—for the spiritually unrefined, fear is sensed as regret for sinful behavior in the past tense. For those on a higher spiritual level, the energy of gevurah is accessed through fear of sin in general, in the future tense. The Rebbe continued his thought with an exhortation to renewed study of Hasidic thought:

For this reason, even now, when every mind is afflicted and every heart is sick, and it seems to people that they cannot speak of Hasidic matters…it is enough for us to hold on to the performance of simple, practical commandments. This is a mistake. First of all, we are bound by the imperative to serve God with all manner of devotion, even in these times. Secondly…a person who entertains such thoughts of fear [of sin]…after periods of introspection he sense will within himself an elevated consciousness, and even joy, because this is a purified fear, a form of “a delight in fear of You,” as we say in the Sabbath song, “Kah ekhsof,” a supernal fear which elevates the individual…

The fear is only the means of preventing sin, yet according to what we have written, it is all one. A person must acquire fear in order that he not sin, a perpetual fear that he not sin. By means of this he will be elevated…as an expression of “delight in fear of You.”

The Rebbe concluded his message with a reference to the Torah reading of the week. Moses was initially hesitant to accept God’s command to go to Pharaoh and demand the release of the Jewish people. God gives Moses as sign—a holy name, “I will be”—so that Moses will be able to convince the Jews that they will be freed:

This is alluded to within Moses our Teacher’s question, who am I…that I should take out [the Jewish people from bondage?]. Since he was the humblest of all people, therefore he began with thoughts such as these: who am I…that I should take out [the Jewish people from bondage].

God responded, it is not that you are not worthy, and it is not that, Heaven forbid, that you have deficiencies, rather the fact that you question yourself is in itself a sign of holiness, Divine worship which illuminates and is drawn from the concept of “God—I will be.“ Until now, a person was incapable of introspection, and said to himself: “until now I was nothing—but from now on I will be.”

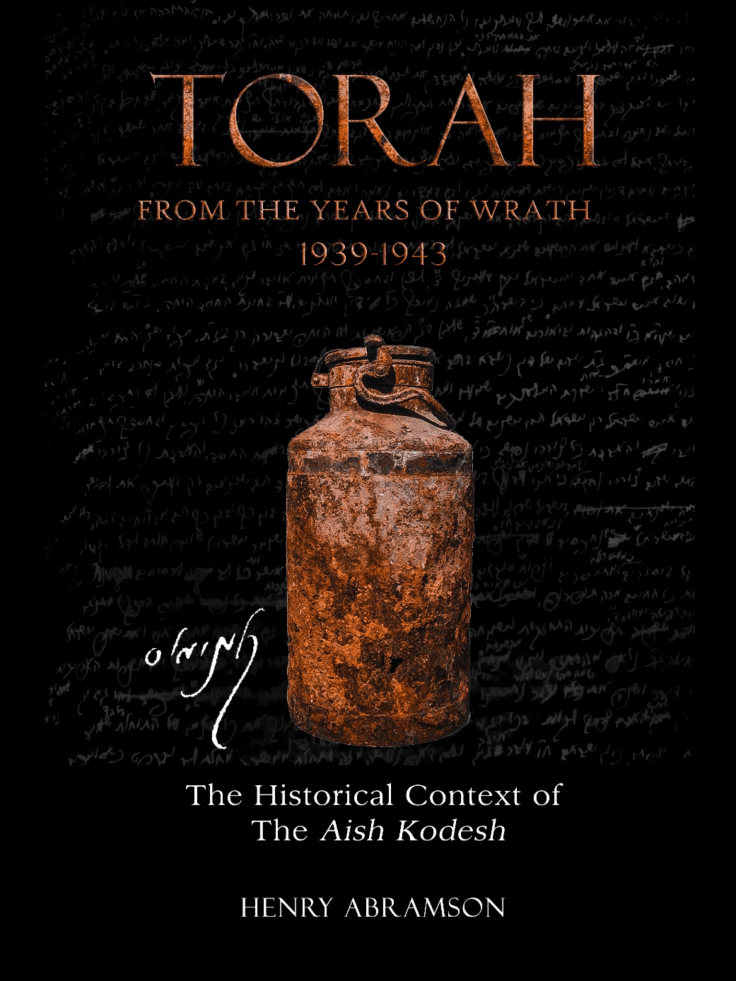

Torah from the Years of Wrath, 1939-1943: The Historical Context of The Aish Kodesh