The last weeks of winter 1942, ironically, represented a kind of plateau for the Jews of Warsaw. The typhus epidemic abated, and the Nazis had established some work facilities (“shops”) that led many to believe that through productive labor, the Jews would endure. The general feeling was, in the words of historians Barbara Engelking and Jacek Leociak, “in the second year of the Ghetto they were sufficiently hardened to survive to the end of the war. No one doubted that the Germans would lose the war; it was only a question of time. What seemed important was to hold out until that moment arrived.” What the Jews did not know, however, was that the worst was yet to come. On January 20, 1942, in a Berlin suburb called Wannsee, the Nazi leadership formally adopted what became known as the Endlösung, or Final Solution: the deportation of Europe’s Jews to specially constructed Death Camps for mass murder.

The Rebbe, along with all the Jews of Warsaw, were of course unaware of the momentous and terrible nature of that conference in Wannsee. On Parashat Yitro (February 7, 1942), the Rebbe delivered an unusually long exhortation on behalf of Shabbat observance, with barely a comment on suffering until the conclusion:

All the suffering, whether in Egypt or even now, even though it leads one to madness, may the Merciful One rescue us, nevertheless it is for this purpose: to crush and overwhelm the human mind, which thinks that it understands and is self-reliant, as in one who increases knowledge increases pain—to crush and overwhelm it in order that afterwards God’s knowledge may be revealed in the innermost spaces of each and every person, and the entire universe.

That crushing, overwhelming pain came shortly thereafter, with the arrival in Warsaw of Jacob Grojanowski, an escapee from the Chelmno Death Camp. His report was as shocking as it was accurate. The observant young man from the Hasidic stronghold of Izbica was deported and forced to work as one of the Sonderkommando, processing the bodies of thousands of Jews and Gypsies murdered at Chelmno, an experimental facility that had been operating since December 1941. Over the course of his ghastly duties, he recognized the corpses of his parents and many of his townspeople before escaping on January 19 and making his way to Warsaw. Recognizing the importance of his testimony, the Oneg Shabbat staff prepared the “Grojanowski Report” and used connections in the underground to convey it to the Polish Government in Exile in London. The Grojanowski Report described horrific atrocities beyond anything experienced in the Ghetto, and detailed precisely how the Nazis had advanced their killing technologies since the mobile killing squads began months earlier:

In order to prepare for the disinfection they were told to undress, men to their drawers, women to shirts. Documents and valuable had to be tied in a handkerchief and all the money sewed in the clothes had to be ripped out, to prevent damage during the disinfection. After these preparations the people were taken to the bathroom through the door leading to the stairs below. Here the temperature fell suddenly because the corridor was not heated at all. To the people’s complaints the German answered politely that they should be patient until they get out of the bath. The bath turned out to be the prepared ramp, to which the unfortunate were rushed with the help of whips, butts and machine-guns, then loaded on the execution van, which was standing on the opposite side of the ramp. The van, into which the unfortunate were rushed, was the size of a big grey truck, hermetically closed and furnished with closely fastened doors bolted from the outside. The walls of the van were covered with tin, small ladders were laid out on the floor, covered with straw mats. Under the small ladders, on both sides of the van, two gas-pipe blowers, closed with a strainer were placed. The two pipes led to the cab, where they were connected to a gas-appliance, furnished with a number of buttons. After the van had been loaded and the door hermetically closed, it drove to a forest, 7km distant from Koło, where the slaughter took place. It was a field surrounded by soldiers armed with machine-guns and in the middle of it ran a mass-grave prepared in advance. These were 5 meters deep, 1.5 wide at the bottom and 5m wide at the top. The van stopped about 100m from the grave. The driver-murderer pressed the buttons of the appliance in the cab and got out. The drivers were SS-men in uniform, with a skull on their hats. Deadened cries and knocks on the walls came from the van. About a quarter of an hour later the driver climbed a ladder and looked through a special eyehole into the van. After checking that all the victims were dead, he drove the van closer to the grave and five minutes later gave an order to open the door of the van. The burial was carried out by some scores of Jewish forced labor grave-diggers. At the order of the commandant of the slaughter place, an SS-officer, they started throwing out the corpses smelling of gas and excrement and lying in great disorder. The corpses were brutally pulled out by hair, hands and feet. The commandant shouted incessantly and struck the grave-diggers. The corpses were piled up, then two German civilians searched the still warm bodies for valuables. The search was very scrupulous. Chains were torn from necks, golden teeth were extracted with tongs. They checked very closely if there were any valuables in female sexual organs and in rectums. Only then were the corpses thrown into the grave, where two Jewish grave-diggers arranged them with their faces to the ground, so that the feet of one were next to the head of another. Six to nine vans were buried a day. Each layer of corpses was covered with earth. From January 17 they also added chloride. Eight grave-diggers, who were dealing directly with the corpses, stayed in the grave all day long. Before the end of the day, one of the officers would order them to lie down facing the corpses and with a hand-machine-gun put holes into their heads.

The Ghetto was paralyzed by the news from Chelmno. Even Czerniaków, the leader of the Jewish Council, noted in his diary that “disturbing rumors are multiplying in the population about expulsions, resettlement, etc.” The Hasidim who gathered to hear the Rebbe’s thoughts on Parashat Mishpatim (February 14, 1942) must have been filled with trepidation. The Rebbe responded with arguably the most powerful sermon of his life.

It is possible that since the Blessed One is infinite, and for this reason is not apprehensible in this world, consequently, the anguish that God experiences over the suffering of the Jewish people is similarly infinite. Not only would it be impossible for a human to endure such great suffering, it would be impossible for a human to grasp the tremendous suffering which the Blessed One experiences, and hear God’s voice saying, “woe unto Me that I have destroyed My house…and exiled My children,” because this is beyond human limitation…

This is also the reason that the world continues to exist and is not destroyed by the anguish and the voice of the Holy One who is Blessed over the suffering of God’s people and the destruction of God’s home: the terrible anguish of the Holy One who is Blessed cannot be made manifest in the world. Perhaps this is also the meaning of the introduction to Midrash Eikhah, in which an angel says, “’Master of the Universe, I will weep, but let You not weep.’ He responded, ‘if you do not allow me to weep now, I will enter a place that you are not permitted to enter, and there I will weep,’ in secret places does My soul weep,’” see there. In the Tana d’vei Eliyahu Rabah it states, “the angel said, ‘it is unseemly for a king to weep in the presence of his servants.’” If it were merely “unseemly” that God weep in the presence of servants, the angel could simply have left God’s presence, and thus God would not weep in the presence of His servants. In light of what we have discussed, the angel’s intent was to say that it is unseemly for a king to need to cry in the presence of his servants—yet since God’s anguish was, as it were, infinite, greater than the universe, thus it could not be made manifest in the universe, and the universe remained unshaken by God’s anguish. Thus the angel said, “I will weep, but let You not weep,” for just as the angels are messengers of God, the agents who perform the Will of the Blessed One, therefore the angel wanted to express God’s weeping, as it were, in the universe, making the weeping manifest in the universe and making it unnecessary, so to speak, for God to weep. For when the universe would hear the sound of the weeping of God, the universe would hear and explode—a spark of Divine anguish would enter into the universe and all of God’s enemies would be incinerated. At the sea, the Holy One who is Blessed said, “my handiwork is drowning in the sea—and you wish to sing songs of praise?” Now, however, that the Jewish people are drowning in blood—shall the universe continue to exist?

The Rebbe’s theological response to the news of Chelmno combined the elements of the sympathetic suffering of God with an apparently anti-theodic position. The incredible persecution of the Jews was like the martyrdom of Rabbi Akiva and the Ten Martyrs of the State, somehow fatefully ordained by the very fabric of God’s universe, as inevitable as it was terrible. Faced with the ineluctable choice between expressing anguish and destroying the universe, God exits the world to an inner chamber in order to seal off the withering impact of Divine rage from the cosmos.

The Rebbe’s following sermon was on Parashat Zakhor, discussing the meaning of the incomprehensible, terrible hatred of Jews by the biblical nation of Amalek.

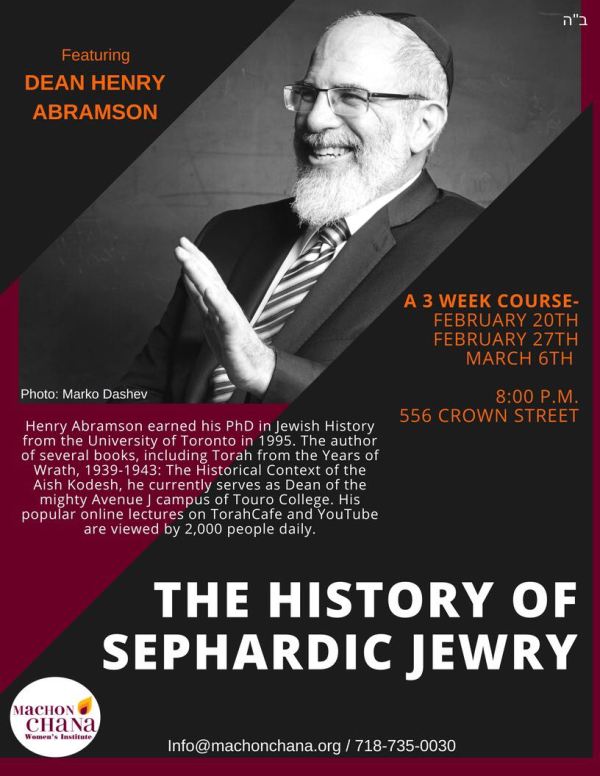

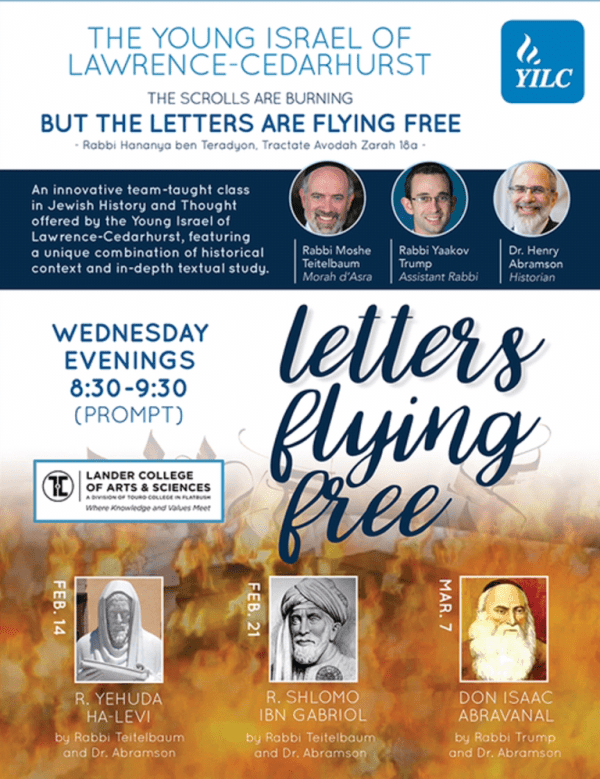

Adapted from Torah from the Years of Wrath: The Historical Context of the Aish Kodesh

Paperback: $24.95. New Hardcover Edition: $34.95, discounted to $29.71.