Tisha B’Av at Young Israel of Fort Lee

Lectures in Jewish History and Thought. No hard questions, please.

I know most of you follow me for Jewish history, not American politics. The Mueller Report, however, carries tremendous implications for Jewish history in Israel and in the US.

I recently read it in preparation for a seminar with Honors students at Touro College (yes, all 400 pages, plus another 300 pages of indictments and other supplementary material), and it’s absolutely clear to me that everyone concerned with the future of the United States and the role it plays in global politics should spend time with this document. Understanding that it’s a heavy lift for many undergraduates (literally and figuratively), I prepared some shortcuts that will allow students to read the unmediated words of the Report in preparation for our 2-hour seminar, and it occurred to me that others might benefit from this small public service.

Here’s an excerpt from my instructions to students.

We will begin the year with a political topic by reading the US Justice “Report on the Investigation Into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election,” known popularly as The Mueller Report. Without doubt, this is one of the most consequential—and controversial—documents of the last half-century, and how it is handled by our representatives will have signal implications for American society as a whole.

I anticipate our debate of the contents of this book will be seasoned and vigorous, but I will remind you all of our commitment to the values of respectful scholarly dialogue. Americans of all political stripes are passionate about the topics treated in the Mueller report, but as members of the Society of Fellows we are enjoined to listen respectfully to our peers and refrain from ad hominem arguments, no matter how much we may disagree with our interlocutors.

The Mueller report is in the public domain at the Department of Justice Website (https://www.justice.gov/storage/report.pdf). The assigned printed copy includes several useful supplementary documents such as the text of the indictments brought by the Office of the Special Counsel.

The Mueller Report deserves to be read in its entirety. Weighing in at 444 pages (with another 300 in the provided printed version) it’s hard to make that demand of an undergraduate student, given the many academic demands placed on your time (I do believe, however, that it is incumbent on all our elected representatives to actually read this Department of Justice report, and not rely on summaries). I encourage you to work your way through the entire text (as well as the 300 additional pages of supporting documents in the Appendices), but I would like to offer the following shortcuts:

3) Whereas Part I speaks to the real and present danger of further foreign interference in our elections, Part II speaks to the future of American political culture, presenting very difficult decisions before us and our elected representatives. Once again I recommend reading the entire Report, but certainly give priority to the following sections:

This promises to be an extremely important and informative opening Honors Colloquium. I look forward to discussing the relevant issues and their implications for our society in the coming year.

If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to reach out.

Sincerely,

Henry Abramson, PhD

Dean

Courtesy the OU Torah Blog, July 17, 2019.

On Shabbat, Parashat Balak, July 20, Jews all over the world will be one step closer to completing the thirteenth cycle of the Babylonian Talmud by completing tractate Erchin in the Daf Yomi cycle. We are all familiar with Rabbi Meir Shapiro, who initiated this worldwide phenomenon–but does anyone ever think of Daniel Bomberg, the Christian who literally put the “daf” in Daf Yomi?

Rabbi Shapiro’s brainchild was born in 1923, a time much like our own. As powerful political, social and economic forces exerted a centrifugal force on the Jews of that era, Rabbi Shapiro understood that the shared study of the Talmud, a core Jewish text, was a powerful way of bringing the fractured Jewish people together under the umbrella of our long intellectual and spiritual tradition. Since then, his innovative program, as boldly ambitious as it was elegantly simple, has united Talmud enthusiasts from Lakewood to London, from Hebron to Hong Kong–literally anywhere in the world, one can find a class that is literally keeping Jews around the world on the same Talmudic page, every single day. Rabbi Shapiro’s brilliant idea, however, could not have occurred without the signal contribution of one Daniel Bomberg.

Born in Antwerp in the late 1400s to a middle-class family of printers, Bomberg received a decent liberal arts education that even included a smattering of Hebrew. This served him in good stead when he went to make his fortune in the bustling metropolis of renaissance Venice, home to a mercantile Jewish population that was recently restricted to the Ghetto.

Printing was in its infancy, but Jews were among the early adopters of this disruptive new technology. The Soncino family were producing beautiful editions of individual Talmudic tractates, confident that the lower production costs of printed Judaica would place books in the reach of average families. Known for their scholarship, the Soncinos took great pains to produce works of lasting quality—but they simply couldn’t print their tractates fast enough to meet the demand.

This is where Bomberg saw his opportunity. Assembling a group of Jewish scholars, beginning with Jews who had converted to Christianity, Bomberg rapidly churned out printed versions of Jewish classics such as the encyclopedic Mikra’ot Gedolot edition of the Torah. The early editions were plagued with errors, and many readers resented the use of apostates in their preparation, but Bomberg had accurately judged the market: the people of the Book wanted lots more books, especially the Talmud, and the demand far outpaced the leisurely supply of the Soncino family of printers.

Bomberg soon replaced his early staff of Jewish Christians with well-regarded Rabbinic scholars straight out of the ghetto. As a Christian, he was also able to negotiate favorable terms for his business, including the right for minimal Church censorship, arguing that ancient texts required preservation in their original state. He even secured rare privileges for his Jewish staff, such as an exemption from the requirement to wear the humiliating Jewish hat.

In a spurt of remarkable productivity, the Bomberg printing house produced a fantastic number of Hebrew books, including the first full printed edition of the Babylonian Talmud. He shamelessly copied the Soncino design, with the commentary of Rashi on the side closest to the spine and Tosafot on the outside of the page, and added many innovations of his own, including one especially important change: page numbers.

Yes, page numbers. As text-oriented as Jews are, we simply never got around to inventing basic pagination (we also lagged behind in punctuation, and as anyone who struggled to learn modern Hebrew knows, we weren’t so hot at vowels, either). Looking at the rapidly evolving conventions of 15th-century printing, Bomberg added a letter “bet” to the first page of text in Tractate Berakhot of his second edition of the Talmud—and the Daf was born.

Since then, much rabbinic and scholarly ink has been spilled in vain, struggling to understand why he didn’t begin with “aleph,” the first letter of the alphabet. The simple explanation is that Bomberg considered the title page as the first folio, or page one.

Although it seems obvious in retrospect, Bomberg’s brilliant introduction of page numbers ultimately set the standard for every single Daf in virtually every single printed edition of Talmud for the next half-millennium. If a given word is on a Bomberg page, it should be on the same page in every future Talmud. Future printers adopted this standardized allocation of precise passages to every page, and there was no messing with Bomberg: even the great contemporary scholar Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz was roundly excoriated in certain circles for altering the traditional page layout in his award-winning edition of the Talmud.

Yet by standardizing the Daf, Bomberg made possible the notion of an international, coordinated study of the Talmud. Rabbi Shapiro literally couldn’t have done it without him.

There’s one basic takeaway message to this story: when tens of thousands of Jews crowd together in January 2020 to celebrate another cycle of Daf Yomi—last cycle, nearly 100,000 Talmudists packed Met Life stadium, and this cycle will likely be bigger—we should recall not only the phenomenal dedication of the Daf Yomi students and teachers, and not only the inspirational message of unity through study proposed by Rabbi Shapiro’s vision, but maybe we should give some credit to the blessing of a philosemitic Christian from Antwerp, Daniel Bomberg.

Dr. Henry Abramson serves as a Dean of Touro College. He is the author of the Jewish History in Daf Yomi podcast, part of the OU Daf Yomi Initiative.

The words of this author reflect his/her own opinions and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Orthodox Union.

Good morning indefatigable students of Jewish History!

I’m happy to inform you that my brief, somewhat strange mini-videos on the history of the Jews in the Talmudic period are now available on WhatsApp, thanks to the amazing efforts of the fantastic team at the OU Daf Yomi Initiative. Special H/T to EC Birnbaum who manages the feed.

If you’e interested in the historical world of the Talmud–biographies, politics, economics, geography, numismatics and culture–please text “history” to 732-606-5934 to be added to the group.

I’m on the WhatsApp myself and look forward to responding to the ensuing discussion. Just remember the cardinal rule: no hard questions, please.

Wishing you all a restorative, spiritually productive Sabbath,

HMA

P.S. For more information on the amazing All Daf app under development, including the phenomenal people who will be joining (like Rabbi Ya’akov Trump!), please visit https://alldaf.oudafyomi.org.

Hello treasured students of Daf Yomi!

On behalf of Rabbi Schwed, EC Birnbaum and the rest of us at the OU Daf Yomi Initiative, I’m grateful to you all for your enthusiastic reception of the Jewish History in Daf Yomi series of videos. We’re working hard on taking the program to the next level with the AllDaf app, which will we hope will be as great as it sounds: All the Daf, All Levels, All Subjects, and so on. I’m proud to be a small part of this larger project.

In the meantime, we’re making a lot of progress with the videos, with tractates Bechoros, Erchin, Temurah and half of Kerisus online at http://www.ou.org/dafyomi and the OU Torah App. Over 150 have been uploaded–a nice start, but we’ve got about 2,650 to go over the next seven years!

I’ve just created a rudimentary General and Subject index to the videos, which you can access by clicking here. We hope to update this index and make it a little more accessible as AllDaf comes online, but for the time being, this index should prove especially helpful for magidei shiur and anyone who wants a deeper, somewhat idiosyncratic and sideways, look into the amazing world of the Talmud.

Enjoy in good health!

A brief overview of the first few centuries of Jewish life in Arles. Part Two of the Jews of Rhone series.

Arakhin, traditionally pronounced “Erchin” in Ashkenazi circles, begins tomorrow. Now’s your chance to join the worldwide community of Daf Yomi learners! Click here for more information on this unusual tractate.

Kudos to Rabbi Moshe Schwed, Director of the OU Daf Yomi Initiative, for putting together this really nice promo for my small contribution, Jewish History in Daf Yomi. Tomorrow we’ll be discussing Daniel Bomberg–the man who put the “Daf” in “Daf Yomi.” Literally.

Archelaus, son of Herod. Okay, probably not really the first Jew, and it wasn’t France then, but close enough.

Click here for my latest guest post on the Orthodox Union Torah blog: “Want to lose weight? Start Daf Yomi.“

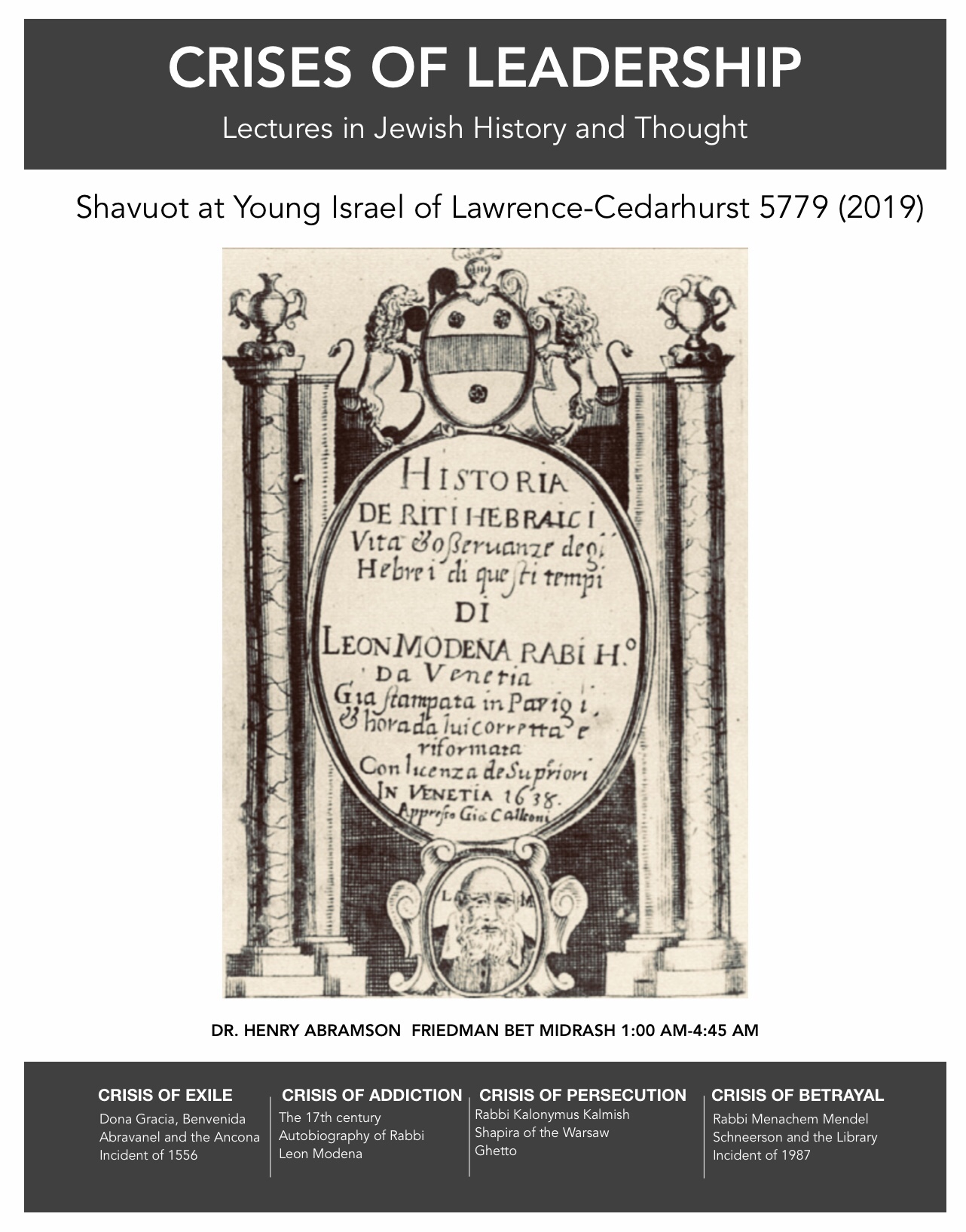

“Leadership” is the theme for our learning this year at Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst. Here’s my small contribution. All are welcome!