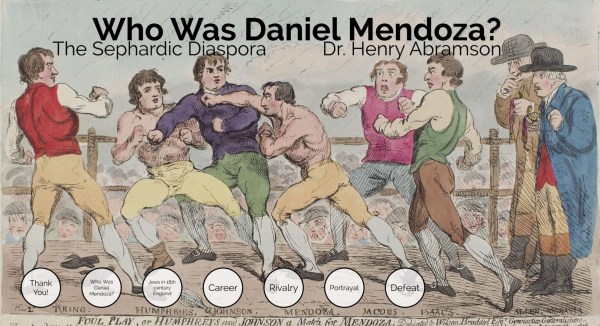

Brief lecture on the life and times of Daniel Mendoza, a Sephardic Jewish champion boxer of the 18th and early 19th century.

Shabbat in the Warsaw Ghetto (Vayakhel 5700: March 2, 1940)

In early February 1940 the Nazis promulgated decrees that prohibited Jews from benefitting from general community charity services. Ration cards were distributed with racial distinctions: Jews received cards with a Star of David marked on them, while Poles and Germans received colored, otherwise unmarked cards. At this early date in the war, hunger did not stalk the ghetto as it would in subsequent years. The ration cards, however, only provided a daily average of 503 calories in the winter and spring of 1940, making the multiple charitable organizations such as the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (the “Joint”) absolutely essential (a black market economy, centered on food smuggled into the Ghetto, would become a major industry in the coming months). Even so, the Ghetto continued to absorb Jewish refugees from elsewhere in Poland, exacerbating the increasingly intolerable living conditions in Warsaw. The memoirs of Mary Berg, then sixteen years old, illustrate the news circulating in the Ghetto:

It seems that in Lodz the situation is even worse than here. A schoolmate of mine, Edzia Piaskowska, the daughter of a well-known Lodz manufacturer, who came to Warsaw yesterday, told us bloodcurdling stories about the conditions there. The ghetto has been established officially, and her family succeeded in getting out at the last moment only by bribing the Gestapo with good American dollars. The transfer of the Lodz Jews into the ghetto turned into a massacre. The Germans had ordered them to assemble at an appointed hour, carrying only fifty pounds of luggage apiece. At the same hour the Nazis organized extensive house searches, dragging the sick from their beds and the healthy from their hiding places, and beating, robbing, and murdering them. The quarter of Lodz which has been turned into the ghetto is one of the poorest and oldest sections of the city; it is composed mostly of small wooden houses without electricity or plumbing, which formerly were inhabited by the poor weavers. It has room for only a few tens of thousands; the Germans have crowded three hundred thousand Jews into it.

The well-to-do Jews managed to escape the Lodz ghetto by various means. Some bribed the Gestapo, like my friend’s family; others smuggled themselves out in coffins. The Jewish cemetery is outside the ghetto, and it is possible to carry dead persons there. Thus some people had themselves boarded up in caskets, which were carried off with the usual funeral ceremonies; before reaching the cemetery they rose from their coffins and escaped to Warsaw. In one case the person locked in the coffin did not rise up again: his heart had failed during the ghostly trip.

On a physical level, the Piaseczno Rebbe contributed to the relief efforts by maintaining a soup kitchen in his Yeshiva and home at 5 Dzielna street. In the spiritual realm, however, he exhorted Warsaw Jews to remain true to the principles and practices of their ancestral faith. On Parashat Vayakhel of the Jewish Year 5700 (March 2, 1940), he focused on the sanctity of the Sabbath day:

Six days you will work, and on the seventh day it will be holy for you, a Sabbath unto G-d. A well-known question in raised in the holy writings: why was it necessary for the verse to command, six days you will work? They would work of their own accord, and thus it would only be necessary to command the Sabbath.

The Rebbe’s question is especially pertinent because Sabbath observance was noticeably declining as Warsaw Jewry struggled to provide for themselves under the new Nazi ration system.

The following interpretation is possible. The Talmud (Shabbat 70a) derives the thirty-nine forbidden forms of Sabbath activity from the phrase these are the words: words, being plural, represent two; the words, represent three; the combined numerical value of all of the Hebrew letters in the word these is thirty-six; producing a total of thirty-nine.

Typical for his analytical style, the Rebbe pushed the reading of this Talmudic passage into a more philosophic bent, strangely prescient of intellectual trends that would dominate western thought decades later:

The rationale behind this numerical calculation of the letters of the Torah is possible because the letters of the Torah are unlike any other letters in any other book in the world. With regard other books, their essence is contained solely within the realm of their intent and intellectual framework. Since it is impossible to write pure thought in itself, therefore letters were employed as mere symbols from which words are built to thoughts and intentions. The letters, however, only have meaning as commonly-held symbols: the choice of representation is entirely arbitrary, and one letter could easily have replaced another letter.

In other words, the shape of letters in other languages is without intrinsic meaning. The form “P,” for example, represents a “p” sound in English but an “r” sound in Russian.

Such is not the case with the letters of the holy Torah. Every letter is precisely as it must be, and could not take a different shape. An alef could not represent a bet and a bet could not represent an alef. This is so because it is not merely the thought and intellectual content of the Torah that is holy—the holiness also diffuses to its physical vessels themselves, namely the letters. As this process of diffusion continues, even the fullness of the letters are suffused with holiness—not only the letters themselves, but even their individual and collective numerical values become holy, and are illuminated by the Torah such that we may learn from them.

The physical embodiment of holiness, in this case into the very shapes and forms of the Hebrew letters, is a major theme in the Rebbe’s thought. He continued:

It is well known from the holy Zohar [3:94, parshat Emor] that the difference between the Sabbath and a festival is that a festival is a “called holy”—one calls it “holy”—whereas the Sabbath is intrinsically holy, as it is written, for it is holy unto you. Furthermore we see that the Sabbath does not have a commandment exclusively associated with it (as Rosh Hashanah has the shofar, Yom Kippur the five afflictions, and Sukot the booths and the four species). The Sabbath is defined by the abstention from specific activities that one engages in during the six days of the week, for the Sabbath itself transforms profane time into sacred time. Furthermore, it is well known that the holiness of the Sabbath even extends into the six days of the week, with the first three days receiving their measure of holiness from the preceding Sabbath and the latter three days from the coming Sabbath. That is to say, not only does physical reality derive holiness from the Sabbath, but even profane time itself receives a measure of sanctity.

The Rebbe concluded his remarks with encouragement, pointing the role of Shabbat in the anticipated Redemption:

This explains the Talmudic dictum, “were the Jewish people to observe two Sabbaths, they would be immediately redeemed.” The first Sabbath refers to the Sabbath itself, and the second Sabbath refers to the weekdays that draw their sanctity from the Sabbath. For six days you will work, [the seventh day] will be holy for you, a Sabbath of Sabbaths: two Sabbaths, because you will thereby draw the holiness of the Sabbath into the other days of the week. Thus with this dictum, the Torah alludes numerically to the thirty-nine categories of forbidden activity—an allusion to the fact that everything is sanctified, even the numerical values of the letters, and from this we may derive Torah.

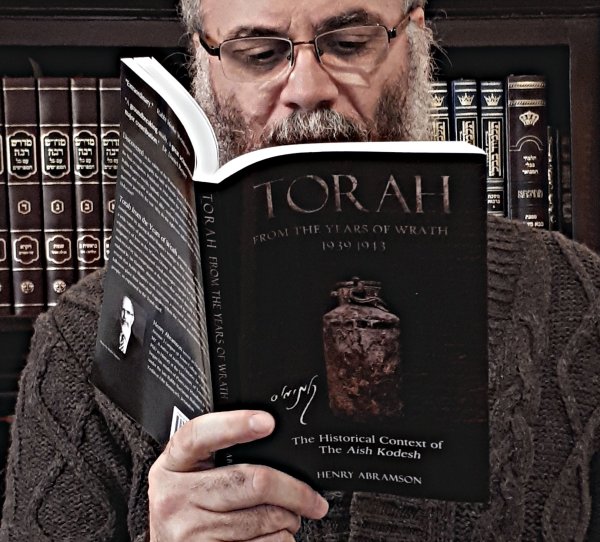

Torah from the Years of Wrath: The Historical Context of the Aish Kodesh

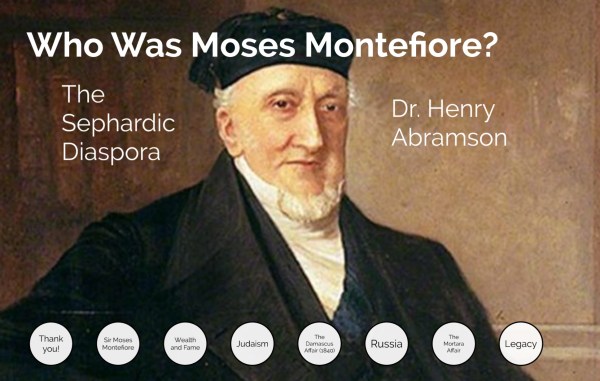

Who Was Sir Moses Montefiore?

Brief presentation on the life and works of Sir Moses Montefiore, an important 19th century Sephardic English philanthropist. Part of the Sephardic Diaspora series.

“Faith is not an argument. It is a conversation.”

“Faith is not an argument. It is a conversation, in which we listen, accept the premises of the interaction, make active choices and contributions, shift our direction as necessary based on the cues we hear, and most importantly, keep the conversation alive and active…Abramson’s work allows us to eavesdrop on one of the most powerful conversations of faith ever recorded.”

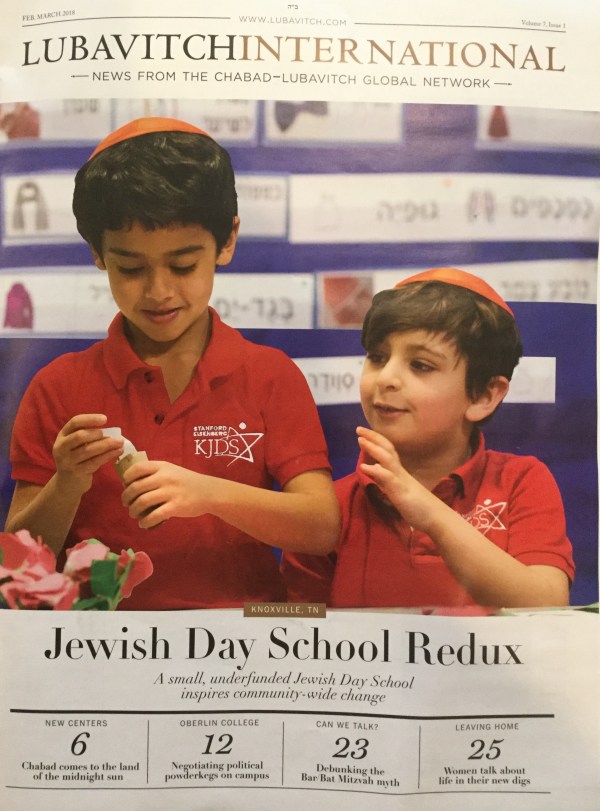

That’s my favorite passage from Dr. Chana Silberstein’s kind review, which I just read after receiving my copy of Lubavitch International (one of my favorite Jewish periodicals). Dr. Silberstein’s sophisticated review is unusually comprehensive, giving a lot of weight to Rabbi Shapiro’s prewar work, and then focussing his thoughts during the war.

The Piaseczno Rebbe was an associate of the Frierdiker Rebbe (the 6th Lubavitcher Rebbe, and the Tanya is one of the most quoted sources in his work, especially the Aish Kodesh. I’m very grateful to Lubavitch International for promoting the unique and powerful thought of the Piaseczno Rebbe to their wide readership.

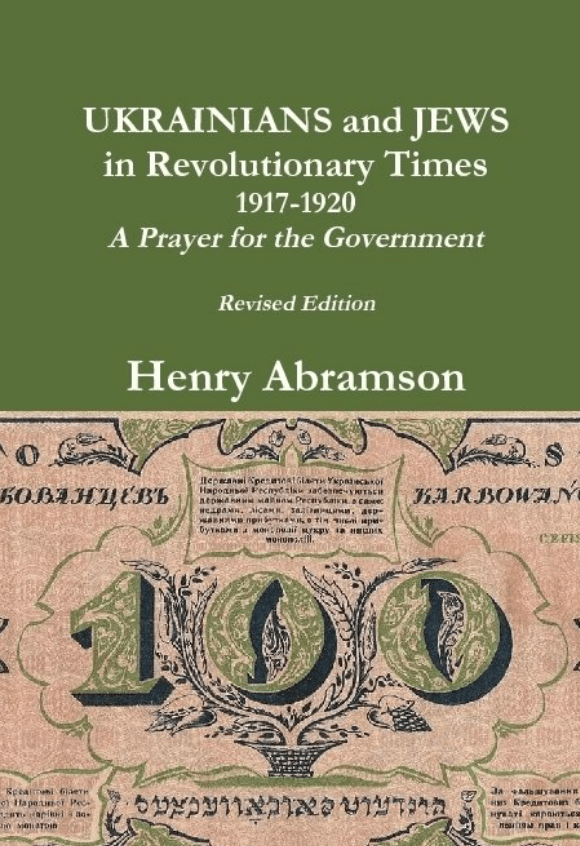

Ukrainians and Jews in Revolutionary Times: New Review

I am grateful for this thorough and kind review of the recent Ukrainian translation of “Ukrainians and Jews in Revolutionary Times” by Oleksandr Zinchenko, published in today’s Istorichna Pravda. If you don’t read Ukrainian (and refuse to read Google translate, which is close enough to the original to be seriously misleading), the revised English edition of the book just came out this week. Available on Amazon in paperback and ebook, and in a specially discounted hardcover straight from the publisher.

Who Was the Chida? The Sephardic Diaspora Pt 3 (Video Online)

Brief presentation of the life and work of Rabbi Chaim Yosef David Azoulay, a fascinating Sephardic Rabbi of the 18th century. Part Three of The Sephardic Diaspora series.

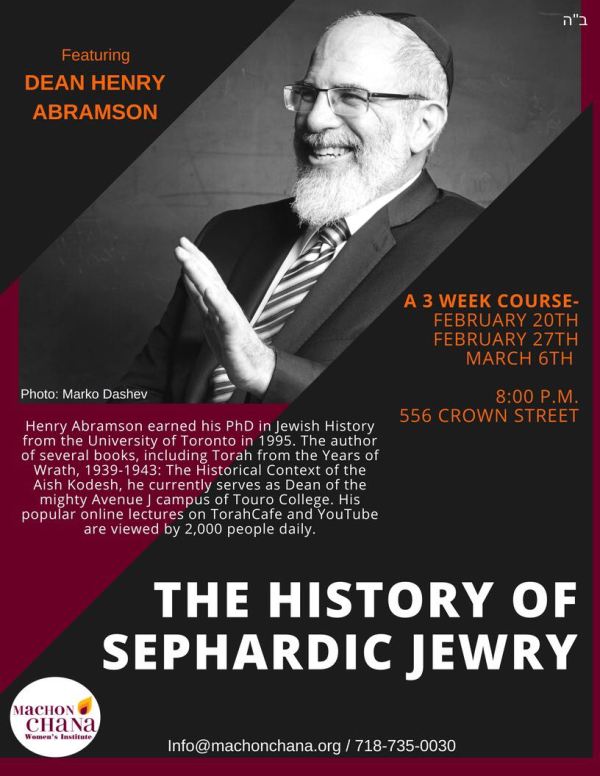

Tonight in Crown Heights: Sephardic Jewry in Reconquista Spain

Tonight at Machon Chana: part two of The History of Sephardic Jewry series. Last week we looked at the origins of Spanish Jewry and the Muslim period; tonight we will focus on the Reconquista up to the Expulsion of 1492.

Sephardic Diaspora Lectures Resume Tonight 7pm

Dr. Michael Chigel on Torah from the Years of Wrath

This is the first time I’ve ever had occasion to be a bit sad to be Henry Abramson‘s friend because I’m afraid you might think I am exaggerating when I tell you how extraordinarily beautiful I find his new book to be, I mean, “Torah from the Years of Wrath.” It’s an historically-charged analysis of the Warsaw ghetto sermons of the Aish Kodesh. I picked it up at the bookstore on Friday and couldn’t put it down all Shabbos until I read it to the end.

I do think you are exaggerating, but I am flattered nonetheless, and would like to share your review with AS MANY PEOPLE AS POSSIBLE.

More than one person has told me that they read the book over Shabbos, and I feel a bit queasy about that. The first chapter, which outlines the Rebbe’s life and work before the war, is certainly valuable and appropriate, but I’m not sure how to react to the idea of reading chapters two, three and four, which deal with the war years 5700, 5701 and 5702 (1939-1943). One the one hand, the Aish Kodesh delivered these sermons on Shabbos, so his Torah–no matter how difficult–must be acceptable on the seventh day. On the other hand, my historical contextualization of the sermons are pretty disturbing, and I avoided researching them on Shabbos and Yom Tov. Many people have told me that they found the book uplifting, though, so perhaps there is room to be lenient. Seems like a question for LOR.

That the style is eloquent and as compelling as a novel, that the scholarship is impressive, that the voice manages to remain the voice of a pious hosid even amid an elegant English style and a scholarly sobriety — all this may go without saying. What makes the book extraordinary is the way it manages to do what very few biographies (if that’s the right word in this case) manage to do, namely to present the life and thought of a single individual in such a way that the entire epoch is put in focus through this one small lens. Henry will no doubt attribute this optic phenomenon to the Aish Kodesh himself, Rabbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira zt”l. But I don’t see how anyone who has read these 1939-1943 Warsaw ghetto sermons of the without Henry’s aspeklaria-type commentary would be able to see the actual epoch in question.

Rabbi Moshe Weinberger shlita mentioned similar thoughts in a private conversation, captured partially in his haskamah to the book: Aish Kodesh was composed with a distinct social purpose, and it is impossible to understand it fully without a grasp of the immediate historical circumstances. Most Hasidic works are less rooted in the specific circumstances of the events of the previous week–in the Warsaw Ghetto, however, the Rebbe’s Hasidim were desperate for a Torah perspective on how to understand the unfolding Holocaust, and his words were carefully crafted to meet their immediate, pressing needs. My role was very simple: I just studied the events of the week, as recorded in voluminous documentation, and then turned to the Aish Kodesh to learn his reaction. The hardest part was envisioning myself as a simple Hasid (or even freethinker) sitting in the Piaseczno Beis Medrash, seeking the Rebbe’s wisdom after suffering the devastating onslaught of Nazi persecution.

Although I’ve read a good number of books on the Holocaust, and more specifically on the philosophical question of “faith after the Holocaust,” this is the first text I have ever read that shows faith itself, emunah itself, in the fray, not as a philosophical problem found among the debris of Auschwitz but as a living torment and spiritual labour. Almost a terrifying vivisection of emunah.

A classic understatement. Mike, you’ve read more than a “good number” of books on this topic. I agree, however–the Aish Kodesh is not a work written in some quiet sanctum, composed with the sounds of a violin floating in the window with spring breezes. “Vivsection” is an interesting choice of vocabulary–not only does Aish Kodesh demonstrate faith in action, almost painfully slow-motion since we know the outcome–it remains alive even today, in the hearts of Piaseczno Hasidim and other students of the Rebbe around the world.

More. It’s perhaps the most terrifying and challenging example of the famous dictum of Rabbi Shneur Zalman: men bedarf lebn mit der tzayt, “We must live with a times,” a dictum that refers in paradoxical language to “time” as defined by the Hebrew calendar and the weekly sedras. The greatest Jewish souls, we know, have always lived inside the text of the Torah with more vitality than they lived inside their own livingrooms. What most people know as “time,” time as defined by the news or by history, is for them dreams and distractions; the only real “time” is that of the weekly parsha, textual time as defined by the Torah. But how many great Jewish souls have shown us what it means to continue living within this order of time, tenaciously, passionately, at all costs, even as the world of things — food, weather, bricks, health, human dignity — crumbles and putrifies all around them?

Powerful words, Mike, and absolutely on point. I wish I had thought to cite this passage in my book! Maybe in a future edition.

For those readers who are less familiar with Chabad chassidus, here’s the passage in full from Hayom yom, 2 Cheshvan: “From a sicha of my father, after the conclusion of Shabbat Lech L’cha 5651 (1890): In the early years of his leadership the Alter Rebbe declared publicly, “One must live with the time.” From his brother, R. Yehuda Leib, the elder chassidim discovered that the Rebbe meant one must live with the sedra of the week and the particular parsha of the day. One should not only learn the weekly parsha every day, but live with it.”

Anyone with a serious interest in his/her Jewish identity and station, especially those of us who remain vigilant to the way that the Holocaust still defines this identity and this station, really cannot afford to bypass this book. It’s mamash a revelation. I love Henry dearly. But this really has nothing to do with him. Well, maybe not nothing.