Kindling the candles for the Festival of Lights, we bless G-d for performing miracles of freedom “in those days, in this time.” The commentators have long resolved the jarring use of apparently non-parallel prepositions: in those days, meaning long ago, but in this time, meaning at the present point in the calendar year. For survivors of the Shoah—and their children and grandchildren the resolution of the contradiction is not so simple. A glimpse of their ineffable perspective is afforded by the writings of Rabbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira, known to his followers as the Piaseczno Rebbe but more popularly as the Aish Kodesh.

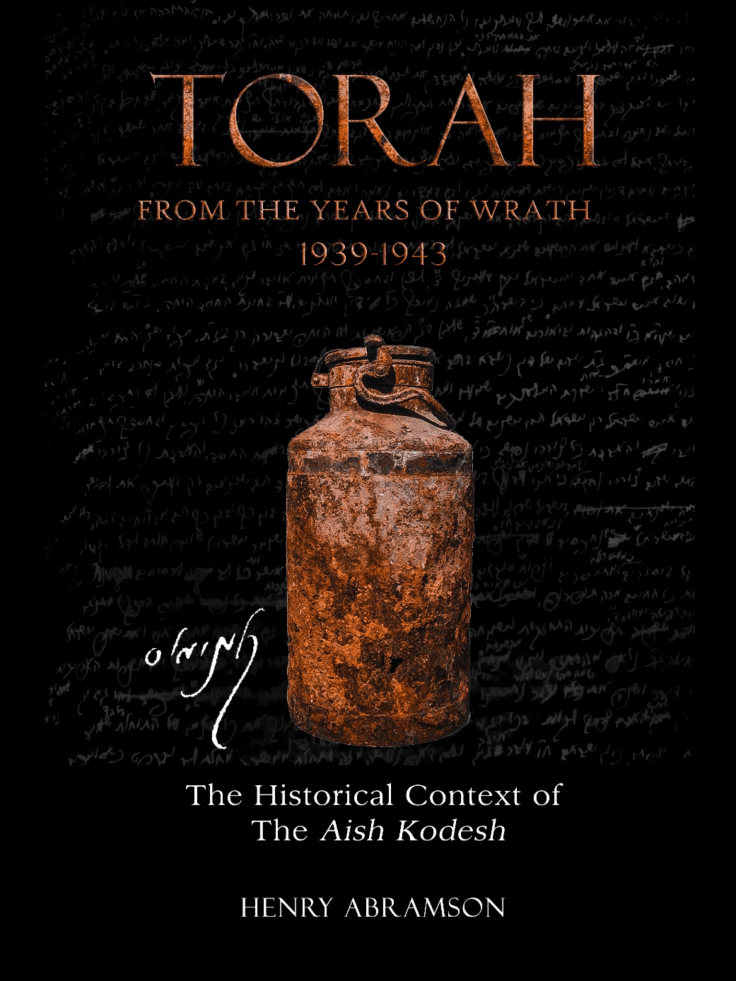

Discovered in a milk can buried in the rubble of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1950, the writings are experiencing a remarkable surge of research interest, including a forthcoming documentary film, widespread translations into multiple languages, a two-volume critical facsimile edition, and my own small contribution which focusses on the historical context of his Holocaust writings. His comments on Chanukah 1941 and 1942 are especially chilling.

The Rebbe meditated on the clashing terms “in those days, in this time” by reflecting on the nature of persecution in Jewish history. The fall and early winter of 1941 was especially brutal. The Rebbe himself contracted and survived typhus, a disease with a 20 percent mortality rate that reached its peak in October with 3,358 recorded infections (the actual number was likely much higher). The price of heating coal became exorbitant as the Nazis rationed the city to finance their military advance into the Soviet Union, and the winter came early and with lethal force that year: the bodies of seventy orphaned, homeless children were collected off the streets on the night of the first snowfall. In November the German occupying force promulgated a decree that imposed the death penalty for Jews who entered the Aryan side city—by the beginning of Chanukah, twenty-three men, women and children were publicly executed, literally for the crime of crossing the street.

The Rebbe’s initial thoughts, as expressed in his drashah on Chanukah 5702, sought to resolve the puzzle posed by the verse by placing the horrific persecutions of 1941 within a broader historical schema. In reality, he argued, looking at the scope of the Jewish experience over the centuries indicated that periodic suffering was to be expected:

It is true that trials such as we are enduring now come only once every few centuries…Historical knowledge has the potential to cause damage, Heaven forbid, if we do not understand history…How can our historical awareness help our minds to understand that which the Blessed and Exalted One knows and understands? Why people are hurt under our current tribulations, more than the trials the Jews endured in the past?…Those people who say that trials such as these never existed in Jewish history are in error—what of the destruction of the Temple, and the fall of Betar?

A year later, the Rebbe changed his mind. Days before Chanukah of 5703 (December 1942), the Ghetto was virtually empty of Jews. Starting with Tisha B’Av, the Nazis began the great deportations, 6,000 Jews per day, to the death camp Treblinka. A population that once reached a peak of half a million was reduced to a few thousand slave workers, including the Rebbe, working in one of the industrial “shops” set up in the city. Together with Jews who hid from the Nazi patrols, this tiny and poorly armed remnant would ultimately launch the heroic Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in the spring of 1943. We do not know what role the Rebbe played in the resistance (although survivor testimonies describe his incredible self-sacrifice in the labor camp Travniki, where he was martyred in November) because his Holocaust writings end with his last will and testament, dated January 1943. The underground group of amateur Jewish historians, codenamed Oneg Shabbat and working under the direction of Emanuel Ringelblum, asked the Rebbe to consign his manuscripts to them. Oneg Shabbat combined the Rebbe’s writings with other studies of the Warsaw Ghetto and buried them in three caches, hoping to unearth them after the war. A lone survivor identified one secret location, excavated in 1946, and the Rebbe’s documents were miraculously discovered four years later. The last archive is still missing.

The Rebbe reviewed his drashot stretching back to September 1939, editing, deleting, and annotating his addresses to his Hasidim. Reviewing his thoughts on Chanukah 1941, he added the following correction:

Note: Only the suffering up to the end of 5702 had previously existed. The unusual suffering, the evil and grotesque murders that the wicked, twisted murderers innovated for us, the House of Israel, from the end of 5702, in my opinion, from the words of the Sages of blessed memory and the chronicles of the Jewish people in general, there never was anything like them, and G-d should have mercy upon us and rescue us from their hands in the blink of an eye. The eve of the holy Sabbath, 18 Kislev 5703. The author.

In other words, the Rebbe corrected his earlier argument. “In those days” was nothing like “in this time.” The genocide that would later be named the Holocaust was a novum in Jewish history, and could not be adequately compared to any other period of persecution in our millennial existence. This is a sentiment shared by many survivors, their children and grandchildren. Nevertheless, despite his troubling conclusion about the meaning of the Holocaust, the Rebbe’s faith remained unshaken. He ends, as do we, with a prayer for the immediate redemption, speedily and in our days.