Brief video lecture on the life and work of Isaac of Vienna (c. 1180-c. 1250), author of the important Or Zaru’a.

Jewish History Lectures Resume Monday Night!

Who Was Isaac of Vienna (the Or Zaru’a?)

Monday, November 5

Who Was the Hatam Sofer (Chasam Sofer)?

Monday, November 12

Who was Max Nordau?

Monday, November 19

Note: this lecture will be held in the beautiful new Machon L’Parnasa campus at 2002 Avenue J, just down the street from our regular location.

Who Was Bertha Pappenheim?

Monday, November 26

All lectures scheduled for Monday nights, beginning promptly at 7:00 pm in the Main Auditorium of the Mighty Avenue J campus of Touro College, 1602 Avenue J, Brooklyn NY 11230 (November 12 will be held at 2002 Avenue J). Lectures are free and open to the public; we encourage support of our brilliant students by offering sponsorships ($500) online at the Friends of Jewish History Scholarship Fund.

For more information write Henry.Abramson@touro.edu or call (718) 535-9333. No hard questions, please.

The Tomb of the Hatam Sofer in Bratislava, Slovakia

Unexpected and unexplained, a phalanx of glass obelisks emerge silently from the earthen mound, punctuating the atmosphere above what appears to be an anonymous tel. Some are transparent, others pebbled and translucent, but all glow with a faint green hue. Unyielding, they stand in rigid formation on the angled surface of the earth. These mute sentinels bear witness to the earthly remains and heavenly destination of 23 holy Jews of Bratislava, Slovakia, as well as the saintly scholar Moses Schreiber, known to generations of his followers as the “Seal of the Scribe:” Hatam Sofer.

Earlier this month I had the privilege of visiting the grave of this remarkable scholar as a historian traveling the Danube River with Kosher River Cruises. Together with leaders of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and 150 Jewish history enthusiasts, we cruised upriver from Budapest, Hungary to Passau, Germany exploring the thousand-year legacy of Danubian Jewry, meeting with representatives of the emergent Jewish communities, culminating in a moving ceremony at Mauthausen concentration camp for the dedication of a plaque to the memory of Simon Wiesenthal, a former prisoner who dedicated the rest of his life to hunting Nazi war criminals and the establishment of the remarkable Museum of Tolerance. Our itinerary was rich and varied, but to my surprise, one of the most powerful moments was the visit to this 18th-century gravesite and its amazing history.

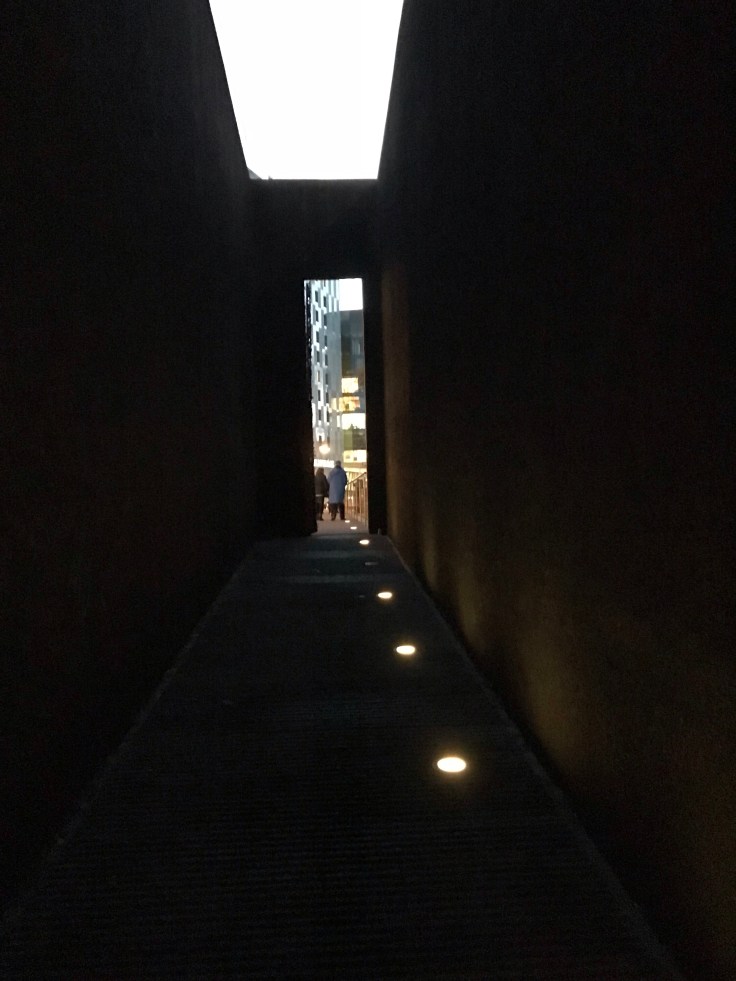

A heavy black triangle juts out alongside the glass sentinels, running at an oblique angle to the road. Inside, a solemn slot-like narrow entrance allows reluctant access to the underground mausoleum where the Hatam Sofer and 22 other holy Jews lie, intact and undisturbed, since the Second World War. The story of their survival in death is as remarkable as the monument built to commemorate them.

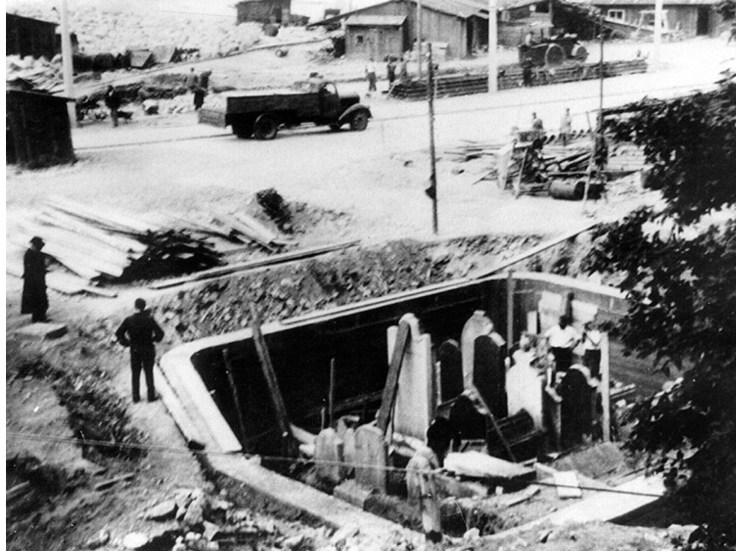

A prewar photograph documents the size of the old Jewish cemetery of the city formerly known as Pressburg. Since the seventeenth century, thousands of Jews lay buried on the bank of the Danube, their tombstones glowing with ethereal light as darkness gave way to dawn every morning. A deeper darkness descended on the community in 1943, when local pro-German fascists confiscated the cemetery with plans to pave it over for new tram lines.

In what would be one of their last acts as a community, the Jews of Bratislava begged for permission to exhume the remains of their ancestors for reburial in the newer Jewish cemetery. For reasons which are unclear, the fascists granted this request and even grudgingly allowed for the protection in situ of the Hatam Sofer’s grave and those that immediately surrounded it.

Money undoubtedly played a role in this begrudging mercy, probably accelerated by a rumor that a terrible curse would befall anyone who disturbed these holy bones. A massive concrete sarcophagus was constructed around the protected tombs, sealing them in below the tram lines that eventually carried Bratislava’s commuters to work every day.

With the fall of Communism, a consortium of philanthropists, Jewish communal leaders and Slovak politicians arranged for the construction of the modern mausoleum designed by the award-winning Slovak architect Martin Kvasnica. The non-Jewish Kvasnica, born in 1958, had previously only worked on one small Jewish project, a kosher kitchen for the emerging Bratislava community, led by Chief Rabbi Baruch Myers, a Chabad shaliach originally from New Jersey.

Researching the complex considerations necessitated by Jewish law, Kvasnica designed a memorial befitting the stature of the Hatam Sofer. Dignified and otherworldly, Kvasnica’s artistic genius literally invites the pilgrim to descend–literally–into the grave of Rabbi Sofer, while at the same time the visitor perceives the ongoing influence of this immortal spiritual giant. Kvasnica’s art demonstrates how not even the Nazis could extinguish the flame of his Torah.

The disciple who first encounters the site may be puzzled by the mute aqua obelisks standing above ground, but that first sensation is dissipated by the unease one feels walking into the black stone entryway. Narrow and confining, open to the sky like a traditional ohel-grave, the floor slopes down to a right-angle entry on the left. A last warning to the visitor is posted there in Hebrew, English, German and Slovak: respect this holy place.

Only one word separates the Hebrew text from the translations: the word lefanekhah. Readers of Hebrew thus receive a nuanced message: “A holy place lies before you.” The site has sanctity for all visitors, but for Jews, this is personal. This is the grave of our revered teacher, a link in the chain of transmission of Torah from Sinai to the present day, a chain that reaches to our own generation.

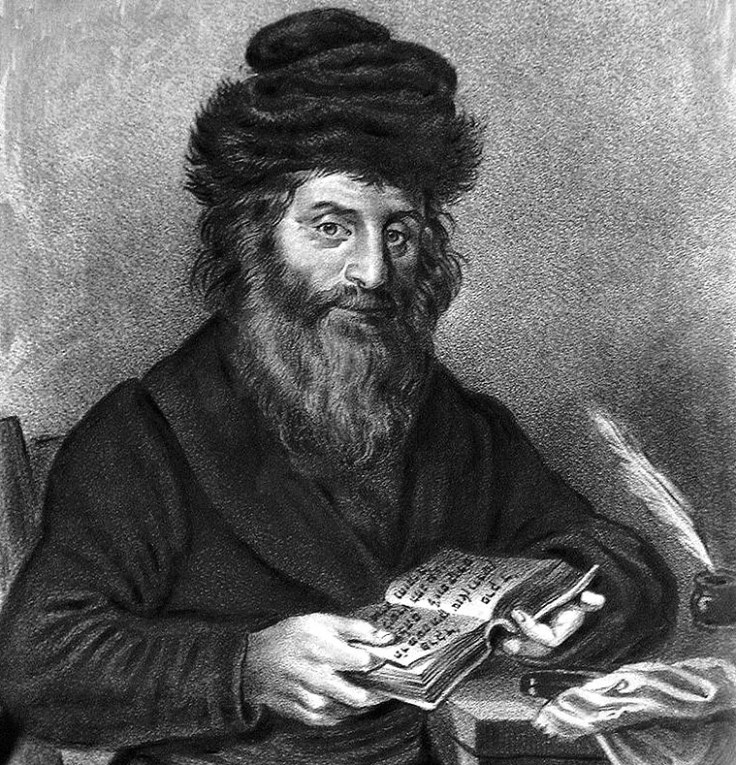

Rabbi Schreiber (1762-1839) was first and foremost a posek, a Rabbi trusted with the difficult task of rendering decisions on Talmudic law. Known for his scholarly erudition, he was particularly distinguished for his articulation of a path for the Jews of his tumultuous times. The rapid political, social and economic changes of his era were nothing less than tectonic in scope, as society wrestled with the possibility of granting emancipation to the Jewish minority. Many Jews openly embraced the political freedoms associated with emancipation, but when it was slow to arrive in German-speaking regions, many opted to simply convert to Christianity to receive the economic, professional and social benefits of abandoning Judaism. Other Jewish communities tried to stem the tide of assimilation by partially adapting to modernity, adopting external non-Jewish mannerisms like dress and language while attempting to remain true to the essential tenets of Judaism.

The Hatam Sofer (alternatively spelled Chasam Sofer) disagreed vociferously. His view of the benefits of modernity was decidedly negative: in exchange for a mess of pottage, the Jews were sacrificing their birthright. Proclaiming a strenuous opposition to the temptations of acculturation, he formed the nucleus of the Haredi approach to modernity, expressed in numerous communities throughout Israel, North America and Europe.

Kvasnica brilliantly captured the enduring impact of the Hatam Sofer’s legacy while preserving the unusual underground sarcophagus created in the 1940s. After descending into the well-lit central chamber, the sloping ceiling is interrupted by what appears to be the protruding lower edges of the green obelisks that rise above ground. The effect is one of strange continuity, as the visitor suddenly recognizes the interconnectedness of the surface world and the subterranean legacy of these spiritual giants. Like intellectual engines, they feed the upper world with their radiant energy–tallest among them is the marker of the Hatam Sofer himself.

The experience of holiness is overwhelming. Standing with my wife, I recited a brace of Psalms in memory of the Jews buried here, along with the many martyrs of the Holocaust.

May the memory of the righteous be a blessing.

The Golden Age of Budapest Jewry: Today’s Excursion with Kosher River Cruises

When the Hungarians purchased their alphabet, vowels were on sale (also plastic sofa coverings and chandeliers). By the time the Poles came around, all that was left were the consonants. This helps explain why we anglophones are so challenged by both languages: in the case of Hungarian, there are just way too many umlauts and diphthongs for even a seasoned polyglot. The Dohany Synagogue in Budapest is a small case in point: it’s pronounced Do-han (rhymes with Roman), concluding with a (basically) silent “y.” Seating over 3000 worshippers, it remains the largest synagogue in Europe a century and a half after its construction, a testament to the size and glory of the Golden Age of Budapest Jewry.

The Dohany Synagogue was a physical demonstration of the might of Budapest Jewry. Jewish migration from surrounding regions would swell the population to 200,000 by the turn of the century, as Jews were attracted by the educational and economic opportunities afforded them by the growing liberalism of Austro-Hungarian policies in the city. After 1867, when Jews were allowed to attend local universities and pursue a variety of educational options, Budapest became a boom city for Jews, who rapidly climbed the various ladders of Hungarian society, hundreds of them even admitted to the nobility for their contributions to the arts, culture, sciences and especially commercial activity.

Together with my wife and 140 Jewish history enthusiasts I toured Budapest for the first time, getting a first-hand glimpse of this remarkable chapter of Hungarian-Jewish history. The Dohany Synagogue is simply astounding.

The synagogue is truly magnificent, representing the most advanced architectural techniques available in the mid-19th century such as the use of thin iron tubing for pillars, combining strength and grace to preserve the airy interior. Denominationally it was part of the Neolog movement, inspired by social and intellectual goals of people like Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsh in Frankfurt and, from another perspective, Zacharias Frankel, considered the father of the Conservative movement in America. The Neologs wanted to make Jewish worship conform to the gentile sensibilities of the day, without doing violence to Halachah (particularly given the opposition of powerful institutions like Rabbi Moshe Sofer’s Pressburg Yeshiva, which insisted on strict adherence to traditional norms). Note for example the pipe organ in the back of the synagogue, symbolically separated from the synagogue interior by a low fence and played on the Sabbath only by a non-Jew (sketchy loopholes that would never fly in Pressburg) Even the parochet hiding the Torah scrolls was lifted with the press of a button that activated an ingenious mechanical clockwork machine.

The size and elegance of the Dohany synagogue contrasts starkly with the tragic, ignominious end of the Jews who sought shelter there during the war, two thousand of whom were massacred and tossed like trash into the adjoining courtyard in the last days of Nazi rule in Budapest. Attempts to identify the bodies were overwhelmed by the colossal nature of the task, and most were simply interred in a mass grave on the spot. Later, families who were fortunate enough to determine the remains of their murdered loved ones erected headstones in the courtyard. It is hard to look upon all these uniform black stones with dates that all end in 1945.

The Budapest Jewish community is thriving, particularly the Hasidic community–at several points in my journey, from the airport to the streets of the reawakening Jewish quarter, I encountered Jews dressed like my brothers and sisters in Boro Park and Crown Heights. Nevertheless, the markers of what has been lost are everywhere in this city. One of the most moving monuments is a series of brass shoes lined up by the Danube River, marking the spot where the Arrow Cross–the indigenous Hungarian fascist party–removed Jewish men, women and children from the protected so-called “International Ghetto” and shot them, tossing their bodies into the blue Danube. In some cases, the sadistic imitators of the Nazis tied three Jews together, shot the middle Jew threw them all into the river, saving bullets and entertaining themselves by watching the two living Jews struggle hopelessly to take one last breath of sweet air.

In a manner reminiscent of the Soviet habit of submerging Jewish suffering into the general “victims of fascism,” the plaques commemorating the horrific murders (erected in 2005, long after the fall of the Soviet Union) do not explicitly mention the Jewish character of the massacre (although the memorial plaque is translated into Hebrew). The precise number of Jews killed in this manner, and their proportion of the total, is still under scholarly investigation, although the remains of victims have been discovered downriver even 60 years later. Visitors to this moving memorial often add their own Jewish markers of mourning–Israeli flags and memorial candles line the bank alongside the silent, ownerless shoes.

We concluded the day with a visit to the castle area in Buda, with its Disney-like architecture and phenomenal views across the Danube. An amazing day–looking forward to sharing my experience with audiences in Brooklyn next month and on the internet.

The day ended on a high note, with the incomparable Howie Kahn performing solo for us when we returned to the ship for the night. I literally can’t say enough good things about this talented performer, whose art and humor elevates us all.

Will the Danube Release its Wartime Secrets?

Jet-lagged, I imagine the inverse of Rabbi Yehuda Ha-Levi’s poetic reflection: I am in the east, but my heart is in the west. Specifically, Brooklyn. It’s nearly 2:00 am here and I am wide awake after a brief but exceptionally deep sleep in my Budapest hotel room.

I can’t stop thinking about the remarkable adventure in Jewish History that awaits me tomorrow. It was great to rejoin the team of Kosher River Cruises yesterday–David Lawrence and Malcolm Green ably managing the complexities of accommodating 140 Jewish history enthusiasts, Rabbi Stuart Weiss organizing our minyan, and Howie Kahn providing late-evening musical entertainment. My colleague David Kraus has been particularly busy planning our ground expeditions, thrown into disarray with the unprecedented drop in the water levels of our conduit.

People here are saying this is the worst it’s been in a century, and many are wondering what it means for the region. Fifteen years ago, in a less extreme drought, the Danube dropped so low that Nazi trucks, driven in the river as the Germans retreated, were discovered by children playing in the newly expanded shallows. Will the current climactic crisis reveal similar archaeological artifacts?

Last night’s introductory lecture went well. Despite our collective exhaustion from travel and some minor difficulty with the a/v equipment, we had a productive meeting , reviewing the medieval settlement of Jews in the region and the basic economic foundations of the villages and cities that punctuated the river’s course from the Black Forest region of Germany to its outlet in the Black Sea. Passage along the River is constrained by a number of locks that normally regulate the water levels for larger craft–what kind of a Jewish tour doesn’t have locks (sorry couldn’t help myself)–but with the drought our ship is stranded upriver in Vienna, so we will have take the first leg of the journey by coach.

Meanwhile, I look forward to sharing the research from this trip with live audiences in Brooklyn beginning November 5, planning to record for everyone as well. Maybe I should try to get some sleep, tomorrow is going to be a busy day.

Tonight in Budapest, Hungary

Hello fellow students of Jewish history!

Today our exploration of Jewish heritage along the Danube River valley begins in Budapest, home to one of the largest concentrations of Jews at the turn of the 20th century. I’m really thrilled to be together with so many people who share my passion for the amazing story of the Jewish people, and once I deal with some of the inevitable jet lag, I’m looking forward to giving the first lecture in the European series tonight (a video version, recorded in Brooklyn, is posted on this site). Tremendous thanks to the great people at Kosher River Cruises for including me in this expedition!

We have one rather unexpected environmental challenge to deal with–the Danube is running at historically low levels this fall, the result of a season-long drought. Most of the tributaries of this mighty river, especially in its lower stretches, are starved for water. Amazingly, the river dipped to 41 centimeters here at Budapest, a terrifying reminder of the dangers of climate change.

We will adapt by staying in the Marriott Budapest tonight, with full kosher catering by Master Chef Malcolm Green, and adapt our itinerary accordingly. More updates to follow.

And for Jewish history fans in Brooklyn–we’re scheduled to begin our live lecture series on Monday, November 5 at 7:00 pm as usual. Please sign up for updates via email at http://www.jewishhistorylectures.org.

Looking forward to learning with you!

HMA

The Saga of Danubian Jewry: Part One of The Jews of the Danube Series (Fall 2018)

Part One of The Jews of the Danube series (Fall 2018). Several lectures to be presented live in Europe this month, planning to return to Brooklyn for more live lectures beginning November 5. Enjoy in good health!

The Murdered Piaseczno Rebbe Had No Dynasty. How Did He Build A Huge Modern Following?

This article appeared, in slightly abbreviated form, in today’s Forward. So many colleagues and friends–fellow students of the Rebbe–contributed moving quotations on the Facebook page dedicated to the Rebbe.

Laura Adkins’ editorship at the Forward is really great, and the final version is certainly more appropriate for the wider audience. If you would like to read the full version, however, I’ve pasted my original below.

May the memory of the Rebbe be a blessing.

***

Seventy-Five Years after his Murder, Rabbi Shapira’s Holy Fire Burns Still Brighter

This month, thousands of unlikely Hasidim will commemorate the martyrdom of one of a lesser-known thinker sometimes called “The Rebbe of the Warsaw Ghetto.” Since the discovery of his buried Holocaust manuscripts in December 1950, fascination with the creative genius and theological heroism of Rabbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira has swelled into a rising tide of interest in unexpected circles.

Many Americans first encountered the Rebbe of Piaseczno (pronounced Pee-ah-SECH-no) through Shlomo Carlebach’s iconic 1981 “The Holy Hunchback” story. Apocryphal and inaccurate, Carlebach’s story nevertheless captured the essential spirit of Rabbi Shapira and some key biographical elements.

Born in 1889, Rabbi Shapira was the gifted scion of the Grodzisk Hasidic dynasty. He led a large Yeshiva in Warsaw and authored a remarkable introduction to Jewish spirituality for children entitled The Obligation of Students (1932). Trapped in the Warsaw Ghetto with the Nazi invasion of 1939, the Rebbe refused offers from the Jewish underground to spirit him to safety, insisting on remaining with the expanding group of followers—Hasidim, mitnagdim and freethinkers—who gathered in his Bet Midrash every Shabbat, hoping to hear words of consolation to help them through the increasingly horrific conditions of the German occupation.

After the massive deportation of Warsaw Jews to their deaths in Treblinka, the Rebbe was impressed into slave labor, first in the Ghetto and then later in the Trawniki labor camp. Before his expulsion, however, he entrusted his notes from those weekly gatherings—as well as his personal spiritual journal and two unpublished sequels to The Obligation of Students—to Dr. Emmanuel Ringelblum’s clandestine Oneg Shabbat archive. The precious manuscripts were sealed in a tin milk container and remained entombed under a building at 68 Nowolipki Street until they were accidentally uncovered by a Polish construction worker clearing rubble from the destroyed ghetto. The Holocaust sermons were published in Israel ten years later under the title “Holy Fire”—Aish Kodesh—the name by which Rabbi Shapira is now most widely known.

Survivors from Trawniki recall that the Rebbe maintained his solidarity with other Jews in the labor camp right to the very end, refusing to participate in an escape attempt if it did not include all prisoners. In the fall of 1943, however, the Nazis implemented a vicious plan called “Operation Harvest Festival” in response to the growing wave of Jewish revolts. The Rebbe was murdered on the fourth or fifth of Heshvan, 5704. The Nazi responsible for overseeing the mass shootings survived the war went into hiding and eventually immigrated to the United States, living peacefully in Queens, New York, until his deportation to stand trial earlier this year.

The Rebbe left behind no surviving children and no Hasidic dynasty, yet his strange mix of followers continues to grow by leaps and bounds. Of course, a Hasidic congregation in Israel thrives around the grandson of the Rebbe’s brother, and in the heart of Hasidic Williamsburg, Rabbi Yoel Rubin’s remarkable chaburah studies the Rebbe’s Torah in The Shtiebl, even though they wear the traditional garb of other Hasidic groups. Manchester, UK has a congregation dedicated to the Rebbe as well.

More surprisingly, in tony Woodmere New York, a synagogue named Aish Kodesh flourishes under the leadership of Rabbi Moshe Weinberger, serving a largely modern Orthodox community otherwise more likely to identify with the Manhattan’s upper west side than with Hasidic Meah She’arim. On the political right, An Israeli settlement in Israel carries the name as well, taken from a murdered Israeli security guard who was in turn named for the Rebbe’s Warsaw Ghetto writings. On the more left wing end of the spectrum, Yeshivat Maharat, more widely known for their training and ordination of female clergy, has Dr. Erin Lieb Smokler as their Director of Spiritual Development—Dr. Smokler’s 2014 dissertation at the University of Chicago was on the Piaseczno Rebbe.

The scholarly world has also matched popular demand with a steady stream of translations and publications since Dr. Nehemia Polen published his PhD dissertation on the Aish Kodesh in 1991. Dr. Daniel Reiser published a remarkable two-volume critical edition that analyzes, in painstaking detail, the numerous strikeouts, additions and emendations the Rebbe added to his manuscript on the Holocaust—a virtual Rosetta Stone to his thought. I have also added my own small contribution in print and video, and forthcoming works include the collected papers of a scholarly conference in Poland and a biography by Shalom Matan Shalom. Dr. Shaul Magid frequently writes on the Rebbe’s Torah in various fora as well.

What accounts for the remarkable popularity of the Rebbe’s works, and why does his thought resonate over such a broad and diverse audience?

Rabbi Shapira was, by all accounts, an exceptional individual with a unique sensitivity to the challenges of every Jew. Many, like Dr. Michael Chigel of Jerusalem, see his spirituality as a form of heroism: he was “a Jew who could not be rattled by time into even that most forgivable form of levity, namely distrust of the Aiberishter [God] on account of personal suffering.” Joshua Rosenfeld testified that “the Rebbe taught us the irreducible nature of faith. Even in the heart of darkness , he uncovered the potency of faith that rests specifically there. In a world that has lost its way, the path of the Rebbe remains the impossible hope at the core of hopelessness itself.”

Many other followers identify with the Rebbe’s searing honesty and authenticity, reflected most clearly in his personal spiritual journal, Tsav Ve-Zeruz, in which he remarkably lays bare all his doubts and fears, without sacrificing his awesome faith in God.

I think most of us, however, see in the Rebbe a warm and understanding guide for personal spiritual development despite adversity, as Nate Fein put it in a recent discussion in Pesach Sommer’s Facebook page dedicated to the Rebbe : “I feel like he’s leading me down a path that not only can I achieve, but one that he himself walked.” Rabbi Yoel Rubin echoed the feeling of many of us when he wrote, “The Rebbe has built a Bridge between the heart and mind, opening up new vistas and horizons. Upon learning his Seforim one can get the feeling of a father taking his little son by the hand, on a roadtrip together to teach him about life and the universe around us…His ideas are like a very deep wellspring which is brought up to the surface, giving it the notion of simplicity and the encouragement of ‘I Believe In You. You can do it.’”

The Rebbe’s Torah from the Holocaust is indeed a remarkable legacy of his genius. For those of us who know his writings well, however, it is his prewar work that gives us the true measure of his stature. I am, for example, not a Hasid—my family background is Lithuanian via Canada, and I prefer the standard Ashkenazi prayer book. Yet when an older man in shul the other day asked me “which kind of Hasid I was”—I immediately, and instinctively, answered “Piaseczno.”

May his memory be a blessing.

Jewish History Lectures Resume!

The Jews of the Danube

Fall 2018 Lecture Series

Lectures in Europe: October 2018

Lectures in Brooklyn: November-December 2018

From its headwaters in Germany’s Black Forest to its final destination in the Black Sea, the Danube River flows through ten countries and over ten centuries of Jewish history. Great cities like Vienna and Budapest punctuate its course through East-Central Europe, the cradle of much of Ashkenazic civilization. This fall we will explore the history of the great Jews and Jewish communities of the region, celebrating the magnificent cultural achievements of Danubian Jewry, commemorating its tragic destruction in the twentieth century—and examining signs of incipient rebirth as the irrepressible, exuberant spirit of Jewish creativity expresses itself along the shoreline in the 21st century.

Following our remarkable exploration of the Douro River, looking for ethnographic remnants of Crypto-Jewish culture in Spain and Portugal, our Fall 2018 excursion into Jewish history will begin with a voyage along the Danube itself with Kosher Riverboat Cruises. Led by Sayeret Matkal veteran David Lawrence and fed by Master Kosher Chef Malcolm Green, we will team with Prague Jewish historian David Kraus, Rabbi Shmuel Weiss and musician Howie Kahn to learn more about the unique experience of Hapsburg Jewry. I am honored in particular to join Rabbis Marvin Hier, Abraham Cooper and Meyer May of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in a commemoration of the life and work of Simon Wiesenthal, culminating in a visit to Mauthausen and Linz.

Returning to the Mighty Avenue J campus of Touro College at the end of October, we plan to continue the discussion in our regular Monday Night Jewish History @ J series, incorporating the intensity and immediacy of local research into the larger perspective of Danubian Jewish History.

Schedule of Lectures

Part One: Europe

(Online versions of these lectures are planned)

1. The Saga of Danubian Jewry (Monday, October 22 in Budapest, Hungary)

2. “Every Sofa Covered in Plastic:” The Glory of Hungarian Jewry (Monday, October 22, in Budapest, Hungary)

3. What is New, is Forbidden:” Bratislava Jewry Responds to Modernity (Wednesday, October 24, in Bratislava, Slovakia)

4. “My Son the Doctor:” Jews and Vienna 1900 (Wednesday, October 24, en route to Vienna, Austria)

5. A Vanished World: Shtetl Culture in the Wachau Valley (Friday, October 26, en route to the Wachau Valley, Austria)

6. Social Change in Danubian Responsa Literature (Shabbat in the Wachau Valley, Austria)

7. The Eternity of Israel is Not a Lie:” Danubian Jewry, the Holocaust, and the 21st Century (Mauthausen & Linz, Austria)

Lecture Sponsored by

Christopher and Ann Marie Bray

in honor of (dedicated to) Eretz Israel

Part Two: Brooklyn

All lectures scheduled for Monday nights, beginning promptly at 7:00 pm in the Main Auditorium of the Mighty Avenue J campus of Touro College, 1602 Avenue J, Brooklyn NY 11230. Lectures are free and open to the public; we encourage support of our brilliant students by offering sponsorships ($500) online at the Friends of Jewish History Scholarship Fund.

Monday, November 5

“Light is Sown:” Rabbi Isaac Ben Moses (the “Or Zarua”) and the Medieval origins of Danubian Jewry

Monday, November 12

“What is New, is Forbidden:” Rabbi Moses Sofer (the “Chatam Sofer”) and the Challenges of Modernity

Monday, November 19

The Other Zionist: Max Nordau and the Vision of a Modern Israel

Monday, November 26

The Untold History of Bertha Pappenheim and the Modernization of Social Activism

For more information contact us at abramson@touro.edu or (718) 535-9333. Sponsorships are available, please visit The Friends of Jewish History.