Chaim Kaplan recorded the mood in the Warsaw Ghetto in January 1942:

The cold is so intense that my fingers are often too numb to hold a pen. There is no coal for heating and electricity is sporadic or nonexistent. In the oppressive dark and unbearable cold your mind stops functioning. Yet even in such a state of despair the human spirit is variable. The call for a free tomorrow rings in your ears and penetrates the bleakness in your heart. At such a moment one’s love of life reawakens. Having come this far I must make the effort to go on to the end of the spectacle. It is hard to foretell who will live and who will die, and it is especially hard to depart from this earth without knowing the final outcome. In the face of this battle of the giants one’s desire to live becomes overwhelming. In spite of the frightful suffering there are no suicides among the ghetto inhabitants. In these fateful hours, we long for life. “Blessed is he who hopes, he will live to see the restoration of Israel!”

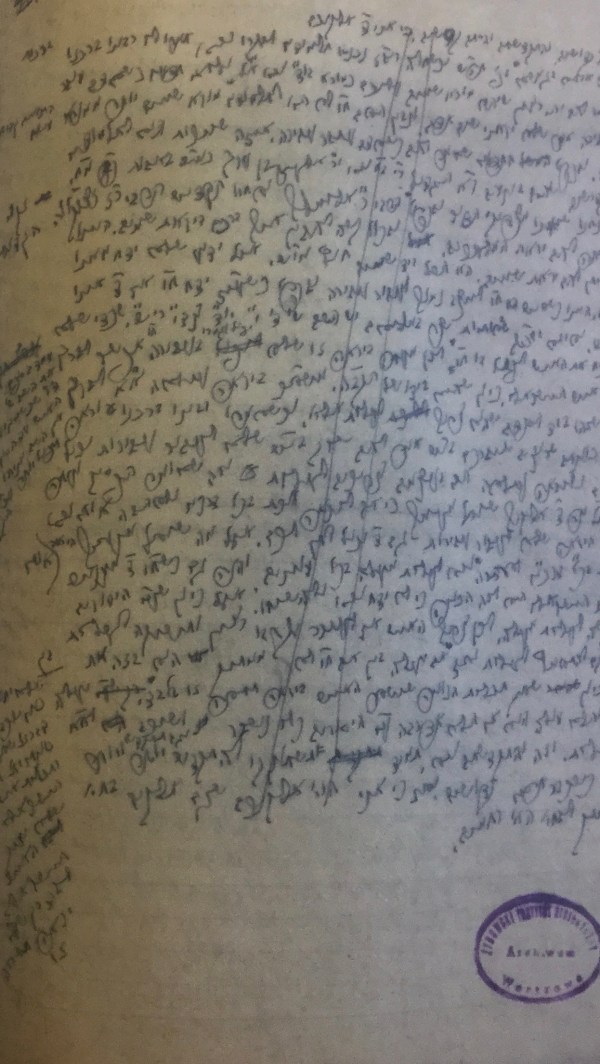

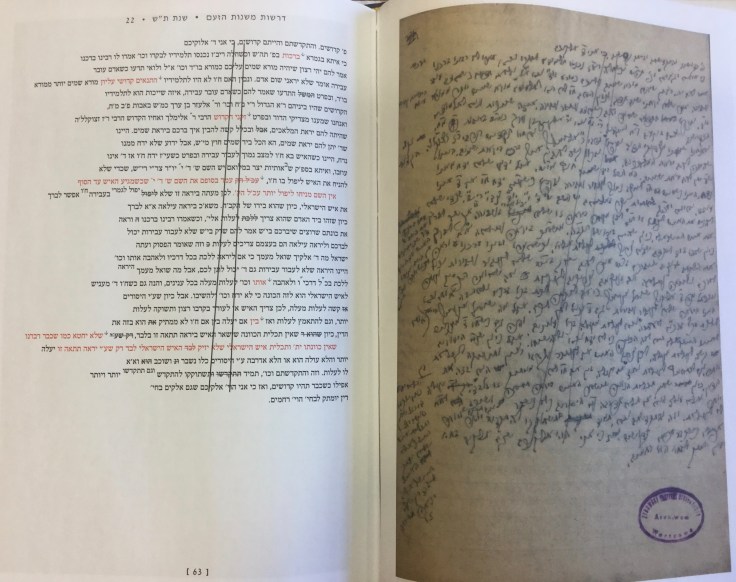

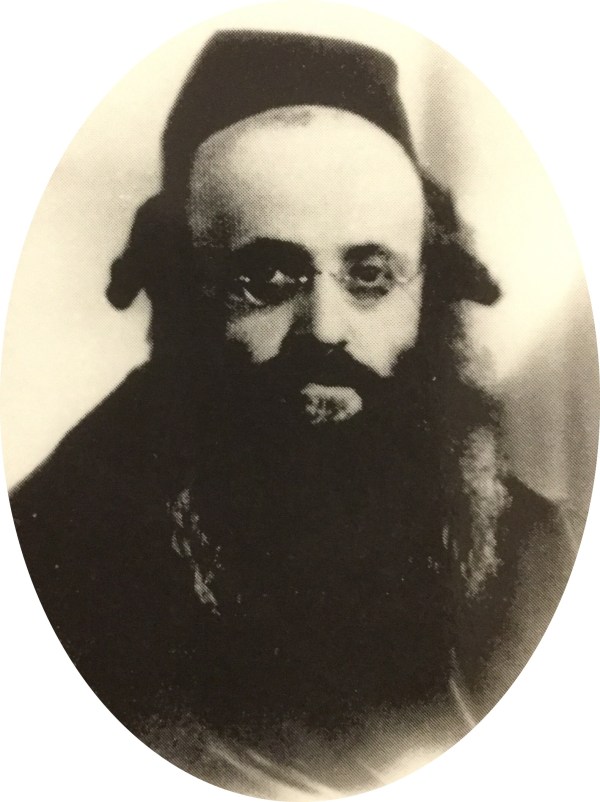

The Rebbe’s message for Vaera (January 17, 1942), reflected on the meaning of cold in the Kabbalistic literature. First, however, he introduced a strange passage from the Talmudic tractate Arakhin:

“Rava bar Shila said in the name of Rav Masneh in the name of Shmuel: there was a magreifa in the Temple…which had ten perforations in it, and each one produced one hundred tones, which taken together produced one thousand tones.” Rashi explains the term magreifa as something which removes [gorfin] the ashes from the altar. We must understand: why did they need a tool used for removing ashes to serve as a musical instrument, and specifically an instrument which produced a thousand tones at once? Furthermore, it is stated in tractate Tamid that the magreifa could be heard as far away as Jericho!

The Rebbe, well-known as a master of the hidden Torah, demonstrated his extensive fluency in the revealed Torah with a number of explanations, but focused on one understanding that specifically related to the suffering of the Jews in the Ghetto—the incomprehensible loss of life over the previous two and a half years of the Nazi occupation:

In tractate Tamid, chapter two, it is stated that the ashes were not removed on festivals, because this was considered the adornment of the altar. That is to say, it was a visual indicator that many sacrifices were offered…All the sacrifices were offered under the principle of in place of his son which was said regarding Avraham the Patriarch…We perceive the great number of animal sacrifices by means of the great amount of ashes which are left behind.

When Jewish people are gathered in by the Divine will of the Blessed One, they rise as offerings to the Blessed One, then only after they are gathered in, do we perceive the magnitude of the sacrifice, in both quantity and quality.

His listeners, many of whom were in extended periods of mourning, no doubt heard the personal message in his words, since the Rebbe has lost his only son, daughter-in-law, and mother in the bombongs of Fall 1939.

Originally, when they were among us, despite how precious they were to us, as the apples of our eyes and the air we breathe, and as much as we had joy and delight in them, nonetheless we did not know how to appreciate what we had, and we didn’t know how to appreciate their value when they were among us. Now that they are lost, may the Merciful One rescue us, we see with greater clarity the magnitude of our loss. The heart yearns and aches, and there is no consolation except for the words of the Holy One who is Blessed to Moshe our Teacher: “this is an element of my design.”

The Rebbe then shifted his message to the concept of cold in Jewish thought and it’s relationship to the yetser ha-ra, or Evil Inclination:

We learn from the Sha’ar ha-Kedushah of Rabbi Hayim Vital, the memory of the righteous and holy are a blessing, that the Evil Inclination is derived from the four elements. Anger comes from fire, pride comes from air, [desire comes from water] etc., and sloth comes from earth. In the holy work Imrei Elimelekh it is stated that the Evil Inclination’s burning desire to perform a transgression can be transformed into holiness and utilized to awaken a burning desire to fulfill a commandment. Such is not the case with the cold Evil Inclination, derived from Amalek, which cannot be transformed into holiness, see there. The Evil Inclination uses the four elements for evil, and the Evil Inclination of Amalek, derived from earth…

We must understand—wouldn’t it be possible to transform [this coldness] into the sloth to commit a transgression, [thereby transforming the Evil Inclination of Amalek into holiness]? This is impossible because the cold Evil Inclination undermines faith, and thus is intrinsically evil. That is to say, as long as the klipah of Amalek is not expressed in laziness and sloth, to undermine faith, then it is possible to use the four physical elements [of the Evil Inclination] for holiness. Since a person’s faith is undermined by coldness, Heaven forbid, then he cannot transform his laziness to transgress into holiness, nor can he transform his burning desire to transgress [into holiness], may the Merciful One rescue us.

What is the relationship between laziness, the element of earth, and the cooling of faith? How does the evil inclination of Amalek use this to damage faith, Heaven forbid? We have already discussed how the faith of a Jew is derived from the spirit of holiness within him, which allows him to have a faith which transcends his intellect and reason. The Evil Inclination can use laziness and sloth, however, to affect the heart, mind and entire body, making it heavy and dragging it down, preventing it from exaltation and elevation, and cleaving to holiness. In this fashion, one’s faith is damaged, may the Merciful One rescue us.

The Rebbe expressed sympathetic understanding for his suffering Hasidim, and connects their self-sacrifice back to the magreifa and its function in the Temple.

When a person experiences tremendous suffering, which breaks him and casts him down, it also damages his faith. Initially, though he does not entertain thoughts that are contrary to faith, Heaven forbid, but he does not experience spiritual exaltation due to his decline. He is prostrate, and it is as if he has become a stone, unfeeling in heart and mind, little by little, damaging and erroneous thoughts occur to him, may the Merciful One rescue us.

Consequently, with the Divine Service of sacrifices, which the Jewish people offered in the fire of holiness, entirely to Hashem, all that remained was the ash, which is an aspect of earth, that did not enter into holiness, and needed to be removed. With what was it removed? With the magreifa that produced music, representing joy and Jewish salvation. Through salvation and joy, everything can be elevated, transforming darkness into light…

This is the intent of the musical sound of the magreifa used for the ashes, which are of the element of earth. Because of their very weight, a greater desire to sing is awakened in them… and by means of the awakening of sorrow, the redemption is aroused, and I will take you out.

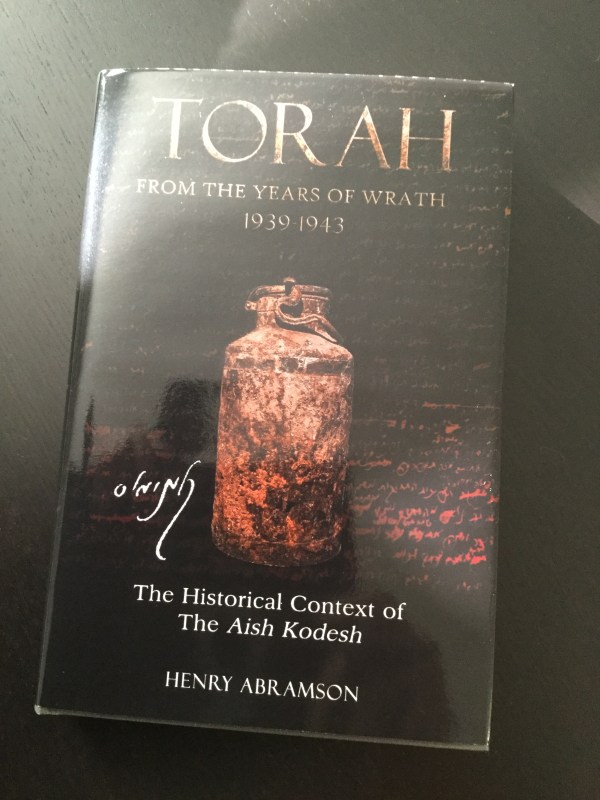

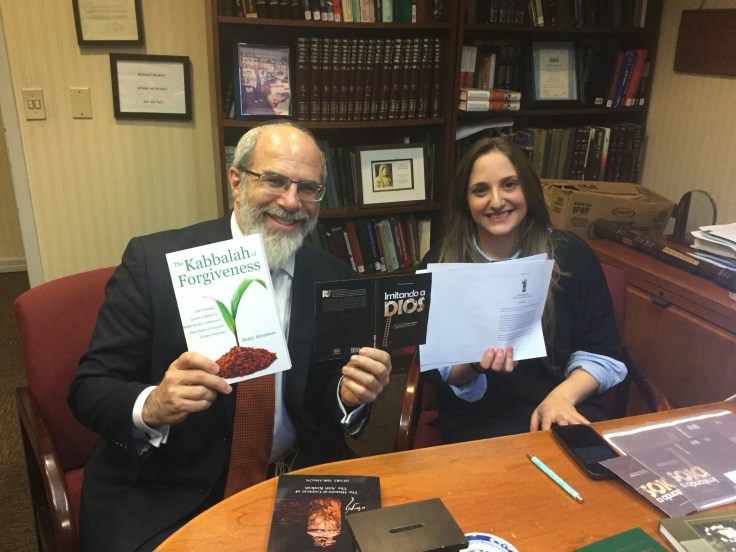

Torah from the Years of Wrath: The Historical Context of the Aish Kodesh