David Gans (1541-1613) was a Rabbinic scholar, historian, and astronomer. A student of Rabbi Moshe Isserles and the Maharal of Prague, he collaborated actively with Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler and left behind important scholarly works.

Lectures in Jewish History and Thought. No hard questions, please.

David Gans (1541-1613) was a Rabbinic scholar, historian, and astronomer. A student of Rabbi Moshe Isserles and the Maharal of Prague, he collaborated actively with Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler and left behind important scholarly works.

People Of The Book: Classic Works Of The Jewish Tradition

By Dr. Henry Abramson

Written with a deep humility that nevertheless could not disguise the author’s brilliance,Sefer HaChinuch remains one of the most thought-provoking halachic studies some 800 years after it first appeared in the Iberian Peninsula. The deceptively simple title, “The Book of Education,” alludes to the anonymous author’s intent: to provide his young son with a basic introduction to the Torah and its commandments. Sefer HaChinuch is therefore an example of the medieval genre of “counters of the commandments” (monei ha’mitzvot), books that list the precise number of positive and negative commandments to add up to the 613 as reported in the Talmud. Many rabbis participated in this scholarly quest, often differing with each other with regard to which act was actually a full commandment, which was only a corollary action, and so on.

Sefer HaChinuch, however, was distinguished by one highly unusual feature: unlike the other monei ha’mitzvot, the Book of Education attempted to answer why each commandment exists. Other scholars, Maimonides and Nachmanides among them, relegated this crucial question to more-sophisticated philosophical works. The Sefer HaChinuch, on the other hand, sought to satisfy the basic curiosity of an adolescent youth. In so doing, he left an intellectual legacy for generations.

The book is often attributed to a well-known 14th-century rabbi named Aharon of Barcelona, but most scholars estimate it was written over a century earlier by an unknown scholar, possibly with the same name and hailing from Barcelona. The author’s attempt to hide his identity is betrayed by a few details in the text, such as the emphasis he places on telling his son to pay special attention to commandments relevant to their family tribe of Levi. He was likely a student of Nachmanides, and possibly wrote the text before the great scholar was banished from Spain in the 1260s.

The book is organized according to the sequential appearance of the commandments in each Torah reading, making it ideal for weekly study. After describing the scriptural basis of each commandment, the text briefly describes how it is observed, who is responsible for performing the commandment (men, women, kohanim, etc.), and under which temporal and conditional circumstances it takes effect (while the Temple was standing, or levirate marriage when the widow is childless, etc.). Finally, each mitzvahconcludes with a remarkably concise and often boldly philosophical description of the “roots of the mitzvah,” meaning its purpose in the Divine Plan.

Some of my favorite sections include the author’s discussions of forbidden mixtures (wool and linen, meat and milk, etc.) that draw upon Kabbalistic ideas about the quality of energies that make up material entities and the spiritually deleterious effects of combining them improperly. The author was also sensitive to the psychological implications of the mitzvot, and is perhaps best known for a theme that runs throughout his work: a person is shaped by his or her actions, not vice versa. By training ourselves in the performance ofmitzvot, even in the absence of a clear awareness of their purpose, we purify ourselves and prepare for ultimate understanding. The Sefer HaChinuch’s purpose as a guide for young people thus retains its evergreen status even for adults living in spiritually and intellectually troubled times.

Henry Abramson is a specialist in Jewish history and thought, serving as dean at the mighty Avenue J campus of Touro College. He may be reached athenry.abramson@touro.edu.

This article originally appeared in the Five Towns Jewish Times on January 28, 2016.

The Jewish Star, January 27, 2016

Identifying himself as a “specialist in the history of ideas,” Abramson, dean of the Lander College of Arts and Sciences at Touro College in Flatbush, explained why Tzfat was important as a major incubator of ideas.

“Tzfat, a sleepy little town in the 16th century, never mentioned in the Tanach, experienced an explosion of Jewish spirituality,” he said. “It went from zero to 100 miles per hour over the course of about 80 years” before dying out. But it affected Judaism for the next 400 years. “It would be like having 100 Nobel Prize winners living here in [Lawrence zip code] 11559. Imagine running into them at Seasons! That’s what Tzfat was like.”

“Most women in Tzfat were as literate as their husbands, except it may have been in Portuguese or Spanish rather than Hebrew,” but there are few documented records of women’s voices in the fellowship, mostly hazy glimpses, Abramson said.

However, much is known about Francesca Sarah Fioretta of Modena, who was thought to have had prophetic abilities and was a dream interpreter. After dreaming that all of Tzfat would be destroyed by earthquakes and plagues, the rabbis coordinated a three day community-wide fast, which was followed by another dream that Hashem had accepted their teshuvah.

In this regard, Fioretta’s “authority was equal to that of men,” Abramson pointed out. This versatile woman “was well versed in the Mishna, Zohar and Torah, and gave classes behind a mechitza to men. There were many possibilities for women at that time.”

“The fellowship was quite concerned with the status of women,” he said. “Even the smallest details of conversations between a couple was thought to have deep kabbalistic meaning. The Kabbalah, as a whole, is a deeply gendered system of thought.”

In the 15th century, 20 years before Tzfat took off, the Iberian peninsula was plagued by the Spanish Inquisition. Many Jews left Spain for Portugal, where they had only a brief respite before moved on to Tzfat. But why Tzfat?

Citing the “Abramson rule of history,” the dean said that “money was certainly a big part of it.”

“If you don’t know the reason why something happened, it’s probably due to money,” he said. “In this case, taxes were dramatically lowered by the Ottomans to encourage international trade. It was like the Las Vegas of its time.”

Asked why Jerusalem was not the preferred destination, he said there was no tax incentive in the Holy City, where 300 years earlier there was barely minyan. “We know this because in 1269, when Ramban was there, they had to bring in Jewish farmers from the countryside to make a minyan,” he said.

For 80 years, Tzfat attracted the finest Jewish minds. Shlomo Alkabetz, known for writing L’chah Dodi, was one of the first to arrive, around the year 1500.

“Alkabetz was known for wandering around the countryside, leaving himself open to spiritual vibrations, and he located many graves of tzaddikim that way,” said Abramson. “Maybe not a scientifically or archeologically sound methodology, but this creative element built up Tzfat’s notability, as well as the new industry of spiritual tourism.”

The elder statesman of Tzfat was Yosef Caro, author of the Shulchan Aruch, whose halachic insights seemed to derive from kabbalistic inspiration as much as conventional book-learning, Abramson said. Moshe Cordovero, Alkabetz’s son-in-law, who authored Pardes Rimonim and Tomer Devorah in the early days of printing, is famous for creating a systematic guide to Kabbalah with chapters and titles, in what we now think of as Western style. Students flocked to Cordovero.

Then the Arizal, Isaac Luria, arrived in Tzfat from Egypt, and he studied with Cordovero until Cordovero died about a year later. Luria himself died shortly afterward. This group was very big on ascetic living and ritual self mortification, but they worked together as a chavurah (fellowship), gathering each night to discuss what they had done wrong during the day and how to fix it.

“Are you aware of the smicha controversy?” Abramson asked his audience. “This too started in Tzfat.” Smicha (rabbinic ordination — literally, laying on of hands) came about at this place and time. In Jewish tradition, Moshe transferred leadership and authority by laying hands on Yehoshua, who did the same with the nevi’im, and so on. In the second Temple period, this was lost as an institution. Yaakov Beirav came up with the idea to reconstitute smicha for the first time in 1,500 years, seeking to endow the title rabbi with a new level of authority and respect.

“His justification was that we are the greatest Jewish minds of the day, and as such are well-suited to determine who should hold rabbinic authority,” Abramson said.

As for parnassah, Abramson cited plentiful and well-preserved Ottoman tax records that indicated the Tzfat rabbis were supported by the community.

“However, the Arizal was an international pepper merchant. The very last thing he said was, ‘Please pay all my creditors’.”

The Ohel Sara Amen Group, in memory of Sarit Marton, a’h, meets each Rosh Chodesh at 8:15 am in Lawrence, with a lecture at 9:30 following morning brochas, Shacharit and Hallel. The group is open to all women, and provides shiurim, classes, and other programming throughout the month. There is no charge to attend. For further information, call 718-327-7040 or email OhelSaraAmen@gmail.com.

This article appeared in The Jewish Star on January 27, 2016: http://www.thejewishstar.com/stories/Touro-dean-eyes-womens-role-in-Kabbalistic-Tzfat,6766

“Nicholas Copernicus’ book “On the Revolution of the Earth Around the Sun” should be suspended…and that all similar works which contain these teachings should be prohibited.” (Bishop of Albano, March 1616)

“Nicholas Copernicus, a scholar of genius…in this domain man is completely at liberty to discover the theory which seems to him to be most consistent with his sense of reason.” (David Gans, 1612)

Interested in learning more about this remarkable 17th century scholar, a student of the Maharal of Prague, and his Jewish views on science? Please attend the first lecture of the Jewish History @ Avenue J series this Monday night at 7:00 pm sharp! Free and open to the community.

Battling unseasonably frigid temperatures, Alexander heroically completed his fourth full marathon in Miami today! A tremendous achievement! Most importantly, with your support he surpassed his fundraising target, bringing in a total of $3,299 for Friendship Circle, helping children with autism and other disorders!

Congratulations to Alexander, and thank you all for participating!

“When I speak, I regret what I say, but when I am silent, I do not regret. And if I may regret my silence once, I regret speaking many times over.”

—Gate 21: The Gate of Silence,

The Ways of the Righteous

Is it possible that The Ways of the Righteous, among the most influential works of Jewish ethics written over the past millennium, was secretly authored by a woman? Proponents of this controversial view advance three principal points to bolster their argument. First, the text was published anonymously. It was not unknown for authors in the mussar tradition to refrain from claiming authorship. It is also sadly true, even today, that women authors seeking publication are forced to hide their gender with a pseudonym, a single initial for their given name, or even pose behind a living male to have their work circulated. The 15th-century appearance of a deeply learned text like The Ways of the Righteous would certainly have aroused suspicion, even notoriety, with a woman’s name on the title page. Second, the text was first published in Yiddish, the vernacular of Eastern European Jewry, but Hebrew was common language of higher learning. Yiddish was known in some circles as der vayber sprach, the “women’s language,” because female literacy was usually limited to this Hebraized version of Middle High German. Third, and most tantalizingly, internal literary evidence reveals frequent use of domestic metaphors and similes. The author often makes reference to cooking, cleaning, and other home-based work that would have been readily grasped by homemakers. Thus if it were true that a woman authored Orchot Tzaddikim, then she would certainly represent the most learned woman since ancient times.

Tempting as this theory is, the arguments rest on relatively weak foundations. Much more likely is the probability that the author was a conventionally educated man with passing familiarity with domestic chores. Research into the several manuscript versions currently housed in the libraries of Oxford, Hamburg, and Budapest suggests strongly that the original version was written in Hebrew, and then translated into Yiddish for a broader, female audience of readers. The mystery surrounding the author, however, should not distract us from the fact that The Ways of the Righteous is a brilliant exposition of Jewish ethics, demonstrating a profound understanding of human psychology and infused with an abiding message of hope for self-improvement.

The book is divided into 28 “gates,” each of which is dedicated to a particular character trait. Versions of the text circulated in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries under the title The Book of Character Traits (Sefer HaMiddot). For each character trait, the author describes both the positive and negative aspects of this particular moral quality, and suggests development of the beneficial and avoidance of the deleterious factors. The influence of Maimonides’ Hilchot Dei’ot is prominent, although an analysis of the author’s source base reveals an exceptionally broad familiarity with the scope of rabbinic writings through the medieval period.

The Ways of the Righteous insists repeatedly that there is no such thing as a bad character trait, only a misdirected character strength. Misunderstood attributes like hatred, cruelty, worry, anger, jealousy, falsehood, flattery, and gossip are treated extensively. Similarly, the text also discusses many positive traits that can be misused, including humility, mercy, alacrity, and repentance. My personal favorites include the remarkably original chapter on silence, and I often turn to the chapter deceptively named “The Gate of Joy” for its moving discussion of faith (bitachon).

The Ways of the Righteous retains evergreen popularity in mussar-oriented yeshivos, especially the Chofetz Chaim movement. It has been adapted into a three-volume children’s book, and a new four-volume translation with commentary was recently completed by my Miami-based colleague, Rabbi Avrohom Yachnes.

This column originally appeared in the Five Towns Jewish Times on Thursday, January 21, 2016.

Source: E-Reading for the People of the Book: How Jews will Adapt to the Digital Revolution

We are living in a Gutenberg moment, plunging wildly into an unprecedented age of transformation whose dark contours obscure the uncertain future. The Information Revolution dwarfs the 18th century Industrial Revolution, which was really great at making things bigger and faster: airplanes travel faster than horses, microwaves cook faster than campfires, but they are still all about visiting relatives or making dinner. Our digital technology, by contrast, thrusts us into change that is radically new. Facebook, for example, evolved out of the idea of a printed student phone book, using the online format to easily expand and update its content. Now, twelve years after it was first launched by students at Harvard, is it anything like a phone book? Even more, is it anything like anything? And for those born after 1995: what’s a phone book?

From the first cuneiform shards to Semitic script, from scribal elegance to mass printing, Jews have always been early adopters. While the Ottoman Empire rejected the first books as ugly, hopelessly deficient replacements for hand-written Arabic calligraphy, Jews scrambled to set up presses, rushing crude editions of precious Hebrew manuscripts into print circulation. Scribal artistry was relegated to ritual documents only, while the less aesthetically pleasing leather-bound books won the day for their sheer utility. Jews recognized that the objective of learning was far more significant than the gourmet appreciation of scribal elegance. The digital revolution, however, poses an unexpected challenge: given the steady migration of books into the cloud, how may observant Jews access them on the Sabbath and holidays, when electronic devices are as banned as brisket in a dairy restaurant?

I humbly predict that Torah scholarship will flourish under the new digital regime. True, it will be harder and harder to purchase conventionally printed versions of less popular works, and Jewish bookstores will have to adapt to an altered supply-and-demand pattern. At the same time, the evolution of radically simple Print-On-Demand technology, combined with the lower threshold of modern self-printing (“indie publishing”) means that more scholars will have more books in perpetual print.

Jewish libraries will look different. Well-studied foundational texts such as the Torah and the Talmud will continue to be published conventionally, probably with many more aesthetic elements and physical improvements to binding and paper quality. Most home libraries will have fewer books, but they will be revered not only for their inherent sanctity but also as objets d’art, cherished family heirlooms like medieval illuminated manuscripts. Other Jewish books, from holy works to contemporary fiction, will migrate almost entirely to tablet-sized e-readers, and consumers will order Print On Demand copies of texts they wish to reserve for Sabbath study. This isn’t the future: it’s been happening for years with the amazing hebrewbooks.org, a site that houses PDFs of rare and out-of-print religious works, as well as an increasing number of works by young independent scholars.

Ironically, print journalism is enjoying a phenomenal renaissance among Jews at a time when secular newspapers are dying, for precisely the same reasons (for those born after 1995, a newspaper is a kind of data-dump printouts of websites so you can read them in places where there’s no Wifi or cell service, like the planet Mars). The physical quality of newspapers and magazines have always concentrated on the ephemeral, leaving more substantive, enduring work to printed books, but what can be more ephemeral than the web? Jews are also consumers of ephemera, but the Sabbath prohibits e-reading, so newspapers fill the gap for the observant.

We will have fewer physical books on the shelves, but our reading will become richer, more diverse, and more sophisticated. Perhaps counter-intuitively, with less hard copies of books, we will need librarians even more than ever to help us navigate an expanding ocean of literature. On the whole, I’d like to echo the immortal words first recorded by Timbuk3 in 1983: “The future’s so bright, I gotta wear shades.” Songwriter Pat MacDonald’s sentiment was intentionally ambiguous, alluding to the flash of a nuclear explosion in a world threatened by global thermonuclear war. Jewish readers may also see the digital revolution as the end of the world, but in reality that rough beast, its hour come at last, slouches towards Jerusalem in an entirely different manner. We will survive this just fine, thank you, and in fact we will emerge from the digital revolution stronger than ever.

Please enjoy this week’s column in the Five Towns Jewish Times!

People Of The Book: Classic Works Of The Jewish Tradition

By Dr. Henry Abramson

“Accustom yourself to speak gently to all people at all times. This will protect you from anger—a most serious character flaw which causes one to sin.”

—Nachmanides’ Letter, translated

by Rabbi Avrohom Chaim Feuer

In the penitential month of Elul in the year 1267, the aged scholar Nachman ben Moshe penned a letter to his son in far-off Aragon. The venerable rabbi, exiled from his home in the Iberian Peninsula, had recently made the treacherous journey across the Mediterranean to Israel, a land which he found almost devoid of Jewish life: After nearly two centuries of war between European crusaders and the local Muslim rulers, even Jerusalem could not assemble a minyan without summoning Jewish farmers from the surrounding countryside.

Rabbi Nachman—known to historians as Nachmanides—would go on to a brilliant second career rebuilding Jewish life in the Holy Land, but that glorious future was unknown when he picked up quill and ink to record what he thought might be his last communication with his children. His classic letter has since been cherished by Jews over the centuries as a heartfelt, profound distillation of Jewish ethics and philosophy.

Nachmanides, a native son of Gerona, was nearly 70 years old when he was summoned by the king to participate in a “debate” on the merits of Judaism with Pablo Christiani, a recent convert to Catholicism who slandered his erstwhile faith and in particular the Talmud. The Disputation was held in Barcelona in 1263 with great pomp and circumstance. Prominent nobles and church officials attended, expecting a pageant that would culminate in the conclusive defeat of Judaism and a mass exodus of dispirited Jews into the welcoming arms of the church.

Christiani had, however, seriously underestimated the sheer intellectual power and erudition of his senior interlocutor, and the debate soon turned into an unexpected rout. Humiliated, Christiani claimed victory nevertheless, but even a cursory comparison of the multiple published accounts of the trial confirm Nachmanides’ decisive victory. The mass baptisms, forced or otherwise, were canceled, and the dignitaries returned to their homes confused and disappointed.

The king, who had no special love for the church, was thoroughly entertained and delighted with Nachmanides’ victory and personally awarded the rabbi 300 gold coins for his efforts. The church was not to be trifled with, however, and Nachmanides was forced to suffer the punishment of banishment for the temerity of ably defending Judaism. He was exiled from Aragon, forced to leave his family and followers. He chose to make aliyah to Israel, and wrote his famous letter upon arrival at the port of Acco.

The letter is some 500 words in the original Hebrew, roughly the length of this article. Despite its essential message of moral instruction, it is written with obvious warmth and affection for the son that he would never see again. The underlying mood of sadness at their forced separation, tempered by profound gratitude to Providence for safe passage across the Mediterranean, is palpable to readers centuries later. The principal theme of the letter is the interrelationship of anger, humility, and the fear of Heaven, with practical suggestions on how to develop self-control and spiritual sensitivity.

Nachmanides concludes with an exhortation that his son review the letter weekly, a custom that has gained such widespread prominence that many prayer books include it as an appendix to the daily Shacharit service. A readable English translation and extended commentary by Rabbi Avrohom Chaim Feuer was published some years ago by ArtScroll under the title A Letter for the Ages.

Dr. Henry Abramson is a specialist in Jewish history and thought. He serves as dean at the Avenue J Campus of Touro’s Lander Colleges and may be reached at abramson@touro.edu.

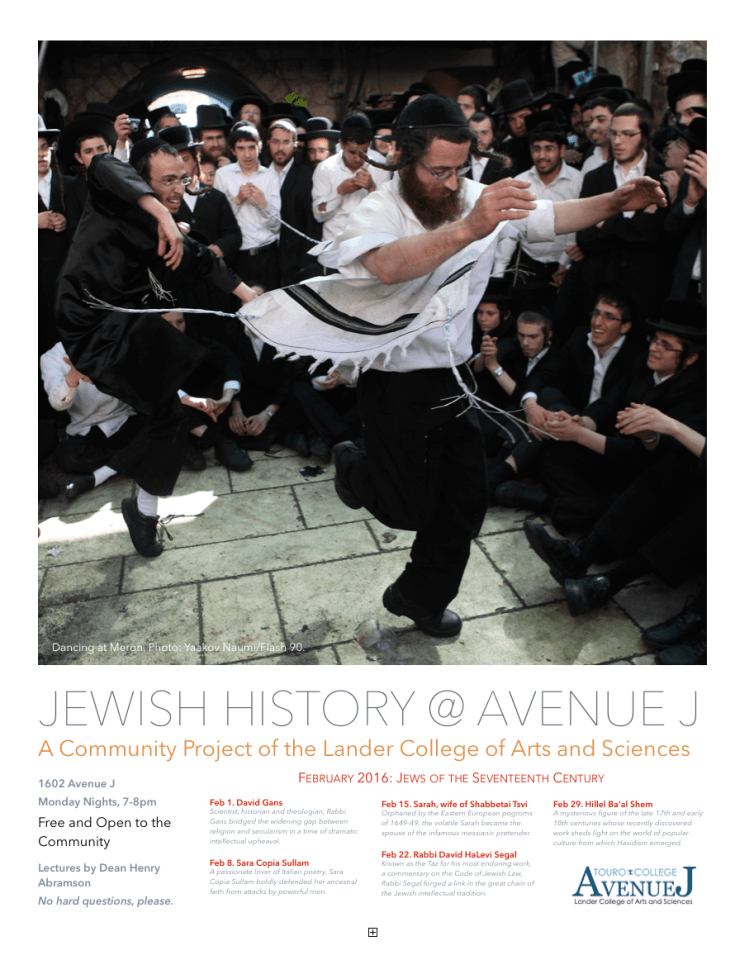

1602 Avenue J

Monday Nights, 7-8pm

Free and Open to the Community

Lectures by Dean Henry Abramson

No hard questions, please.

Feb 1. David Gans

Scientist, historian and theologian, Rabbi Gans bridged the widening gap between religion and secularism in a time of dramatic intellectual upheaval.

Feb 8. Sara Copia Sullam

A passionate lover of Italian poetry, Sara Copia Sullam boldly defended her ancestral faith from attacks by powerful men.

Feb 15. Sarah, wife of Shabbetai Tsvi

Orphaned by the Eastern European pogroms of 1649-49, the volatile Sarah became the spouse of the infamous messianic pretender.

Feb 22. Rabbi David HaLevi Segal

Known as the Taz for his most enduring work, a commentary on the Code of Jewish Law, Rabbi Segal forged a link in the great chain of the Jewish intellectual tradition.

Feb 29. Hillel Ba’al Shem

A mysterious figure of the late 17th and early 18th centuries whose recently discovered work sheds light on the world of popular culture from which Hasidism emerged.

Questions about college? Like to know more about our academic programs, financial aid and scholarships, earning college credit while learning in Israel? Attend our Virtual Open House, this evening from 7-8 pm!

Please click here to RSVP (or visit las.touro.edu) and we will happily send you the link to view the presentation and participate in the question-and-answer session.

Looking forward to seeing you!