Please click here to read the review at The Jewish Star.

The name and history of the Aish Kodesh in our community is well known. This legacy from the tragedy of the Warsaw Ghetto of one of its towering leaders, Rebbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira, the Aish Kodesh, has been taught to us by the example of Rabbi Moshe Weinberger of Woodmere whose shul is dedicated, by name, to the Aish Kodesh.

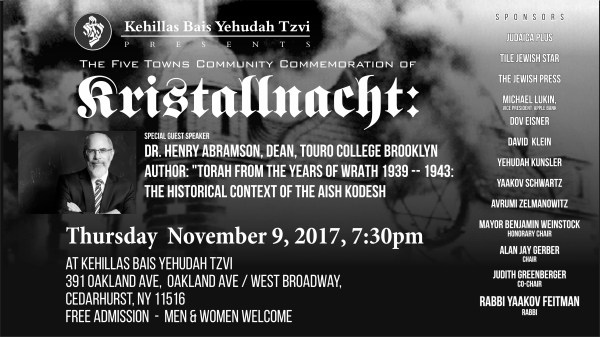

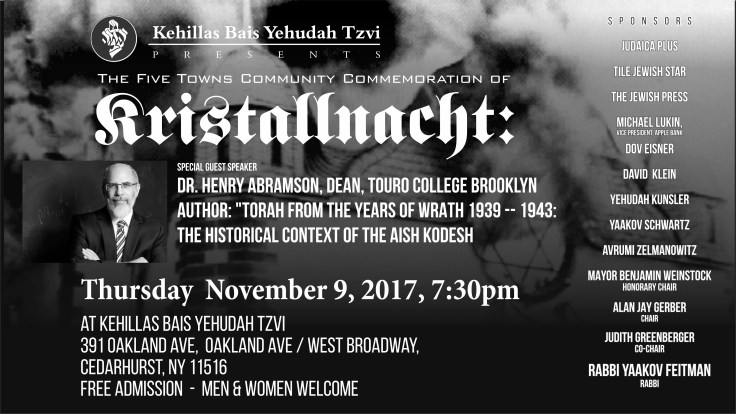

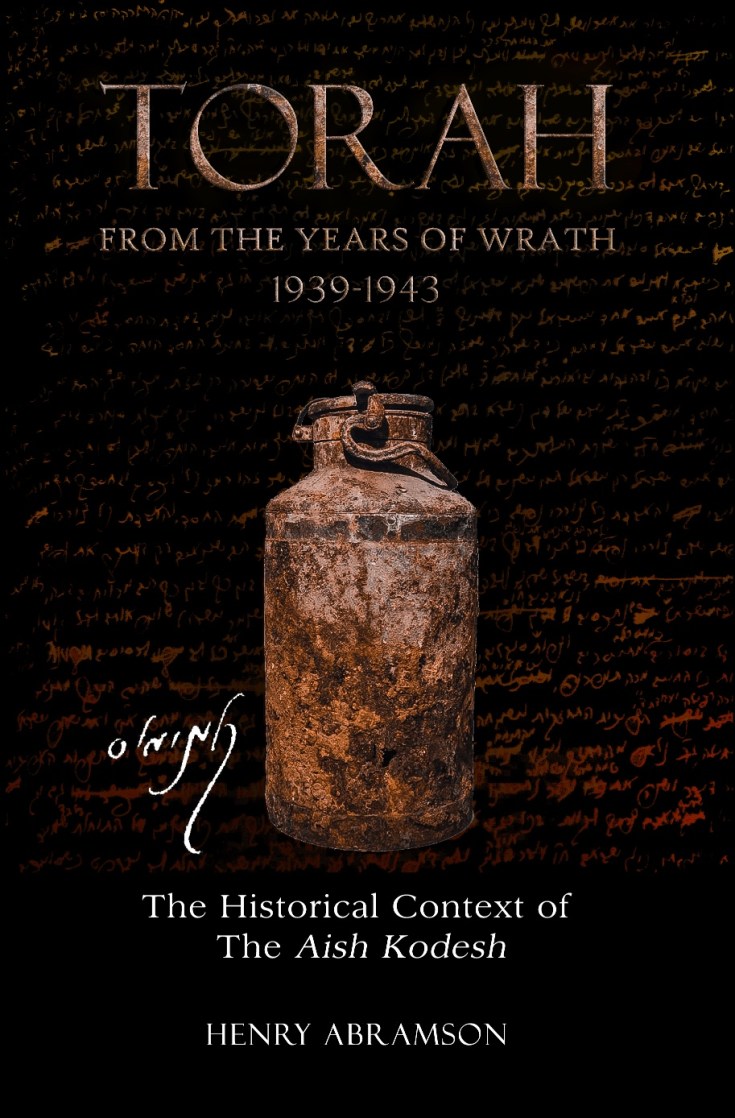

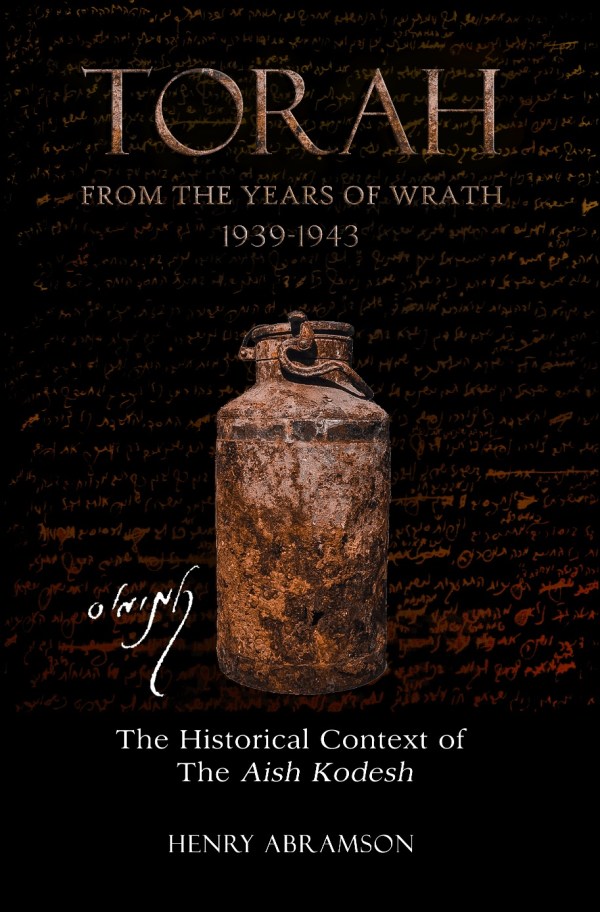

Recently a new book was published, authored by the distinguished scholar and educator, Dr. Henry Abramson, dean of the Brooklyn campus of Touro College, themed to the legacy of the Aish Kodesh, titled, “Torah From The Years Of Wrath 1939 – 1943: The Historical Context of The Aish Kodesh.”

This work receive the following approbation from Rabbi Weinberger:

“I am indebted to Professor Henry Abramson for his extraordinary study of Aish Kodesh, and his bringing to life the heart-wrenching, poetic world of the great tzaddik and martyr, Rebbi Kalonymus Kalmish Shapira of Piaseczna. May this work be a merit for him and his family and may we all be privileged to be uplifted by the teachings of one of our most inspired masters.”

The following guest review was written by Rabbi Pesach Sommer, a member of the Judaic Studies faculty at the Ramaz Middle School in Manhattan. A musmach of Rav Zalman Nechemia Goldberg, Rabbi Sommer is also much involved with project Makom, and is a writer, blogger, and an accomplished speaker. The following is his take on Dr. Abramson’s work:

“Without lifting up a gun or molotov cocktail, Rav Shapira committed some of the greatest acts of heroism of World War II.

“While experiencing much personal trauma and suffering, the rebbe managed to offer words of encouragement and hope to unknown scores of Jews, religious and irreligious, chassidim and misnagedim alike, who, like him, were trapped in the Warsaw Ghetto. Those who have read the rebbe’s words of Torah delivered on many Shabbas and holidays between the years 1939 and 1943, the written record of which miraculously survived after being buried in the ground before the ghetto was destroyed, have been inspired by his uplifting words delivered under the most trying of circumstances. Still, until recently, readers had an incomplete picture of his words.

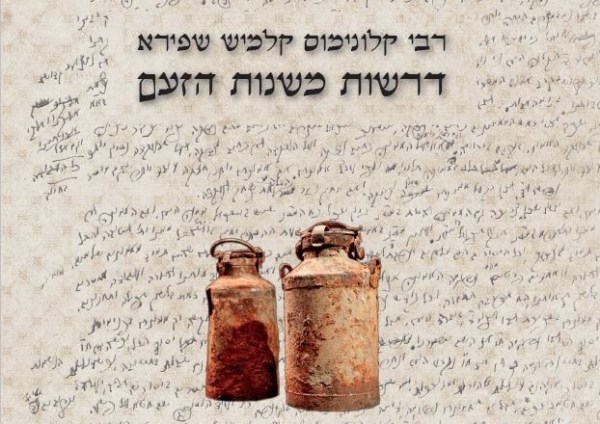

“After being discovered in the rubble of the Warsaw Ghetto, the rebbe’s derashos were published by some of his surviving students in a work titled ‘Aish Kodesh.’ While they did their best to give over the rebbe’s words as accurately as possible, there were various typos and other errors that made it into the sefer. Recently, Dr. Daniel Reiser of the Herzog Academic College and the Tzefat Academic College published an incredible two volume critical edition of the rebbe’s derashos which is destined to be the one used by anyone interested in learning the rebbe’s wartime Torah.”

Further on in this narrative we are informed of the following: “While his divre Torah provide comfort and hope to those who are suffering, the reader is largely left unaware of the particular events which led the rebbe to say what he did each week.”

To fill this void, Dr. Abramson wrote his book to further teach us of the rebbe’s purpose and motives that brought about his holy teachings.

Rabbi Sommer continues: “After an opening chapter which provides biographical information about the rebbe from before the war, there are three chapters each of which concentrates on a year from the war, what the rebbe spoke about at that time, and which events led to the choice of topic. Through Abramson’s thorough scholarship and compelling writing, the reader’s eyes are opened as the divrei Torah are connected to the rumors which might have been going through the ghetto that week, a new policy which led to additional suffering, or the narrowing of the parameters of the Warsaw Ghetto.”

Further on we learn of the following: “The book concludes with a fifth chapter where he addresses something which has long been a point of contention among scholars. As one reads the rebbe’s words from during the war, one notices a shift in his outlook. While at the beginning of the war the rebbe seemed to see the suffering that he and his fellow Jews were experiencing as fitting within traditional explanations for earlier tragic eras, where teshuva is required, it is clear that at a certain point he recognized that the level of suffering was way beyond that which could be explained by seeing it as an extension of earlier tragedies. The rebbe no longer suggested that those who were listening to him could change things by returning to G-d. Instead, he tried to figure out how a believer should view this sui generis experience.

“While unfortunately certain academic scholars have used this change to suggest that the rebbe [G-d forbid] lost his faith, Abramson shows the absurdity of such a claim. He makes a conclusive case that while the rebbe struggled to make sense of the atrocities that the Jewish people were suffering, he remained what he had always been, a person with deep and enduring faith.”

Dr. Sommer concludes his essay:

“Dr. Abramson has written a book which is destined to lead to an increase of study of the rebbe’s Torah and thought in both the academic and Jewish world. His is a work which while maintaining high academic standards and containing ideas which will advance the field, is at once accessible to the non-scholar, and written in an engaging and compelling manner.

“Especially for the reader who is looking for a work which contains both Torah and Avodas HaShem, along with serious scholarship, I can not recommend this incredible book strongly enough.”

I cannot agree more with Rabbi Sommer’s gracious and heartfelt conclusion.