Hello fellow students of Jewish history:

I am proud to tell you that I was recently nominated for a prestigious Covenant Award, in recognition of my work teaching Jewish history on the internet. I just learned, however, that the office has not yet received sufficient Letters of Support necessary to consider my candidacy–and the due date is tomorrow at 5 pm! (Thursday, December 13).

So here’s where you can help–if you have found these classes worthwhile, would you consider writing a letter of support and sending it to me directly at hmabramson@gmail.com? I will assemble them into one document and submit them to the Covenant Foundation for their consideration. The earlier the better.

I’ve never crowd-sourced letters of recommendation before, but in truth, it has a certain poetic irony to it–after all, the whole point of my efforts are to spread interest in Jewish history world wide, so asking the Web audience for support is completely consistent.

I’m attaching the two essays I had to write for the award, a Statement of Motivation and a Statement of Purpose.

If you have the time to spare for this letter, I would really appreciate it.

Thank you!

Henry Abramson

Hmabramson@gmail.com

Statement of Motivation

I grew up as the only Jewish child in Ansonville, a tiny settlement in northern Ontario located about 175 miles below the southernmost range of polar bears. (My grandfather was part of a clutch of Lithuanian Jews who fled Russia in 1904 to set up small businesses in the Canadian north. The community peaked in the 1940s; by the time I was born the only Jews left were my parents and an elderly second cousin in nearby Montrock.) My earliest experiences with Jewish education involved the weekly drive south to Timmins, where a peripatetic melamed taught a Hebrew class for the Jewish children scattered throughout the northern communities. I don’t remember much from those interminably long Sunday mornings, except for one thing: I was inspired by Jewish history right from the get-go.

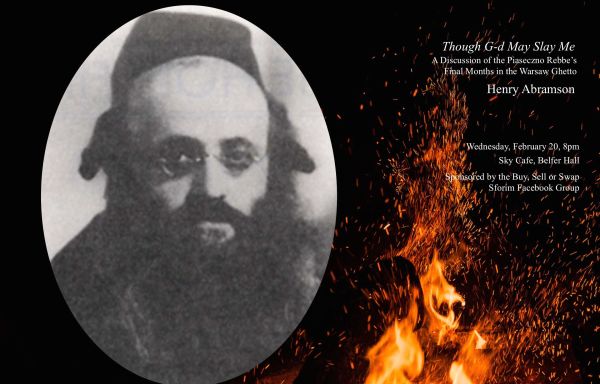

I remember attending a matinee performance of The Ten Commandments at the Cinequois Theatre, watching transfixed as Charleston Heston as Moses went toe-to-toe with Yul Brynner’s Pharaoh. I remember sitting at my mother’s pink formica kitchen table and lovingly curating my scrapbook of Jewish history photographs cut from the Canadian Jewish News (on amud alef, a page dedicated to the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, on its verso photographs and maps of the Six-Day War). I remember summer afternoons, fishing in the Abitibi River while daydreaming about Jewish history, and marveling at the incredible resilience of my people, my history—and I always wondered what part I would play in our collective destiny.

When I turned ten, my parents arranged for me to live briefly in Toronto and train for my Bar Mitzvah. The expense and difficulty was not a simple matter for them, and in recognition of their sacrifice I dutifully attended Eitz Chaim Yeshivah every afternoon after public school, coping with the introductory Hebrew curriculum but showing special interest when my gifted and passionate Jewish educators related historical stories from the midrash. After my Bar Mitzvah, I returned home to learn a much more consequential lesson in Jewish identity: the inevitability of antisemitism.

I had expected to pick up where I left off with my childhood playmates. Instead I was greeted with snarls of “dirty Jew” or the more colorful French term maudit Juif: “cursed Jew.” I struggled with their stark transformation, both intellectually and on a physical level in the form of regular fist fights. The experience scarred me. When I eventually returned south to attend the University of Toronto, I was fortunate to find intellectual solace in the thought of the late Professor Emil Fackenheim, a scholar whose research on the metaphysical significance of Jewish history influenced me deeply. I was proud to be among his youngest protégés and followed him briefly to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

After earning my degree in Philosophy, I immediately found gainful employment as a ski instructor. Not especially rewarding from a Jewish perspective, but Providence wasn’t ignoring me—it was on the slopes that I met my wife, also an instructor. Her connection to Judaism was even more attenuated than mine; yet, as our relationship progressed, she quickly outpaced me. Since then our life together has been a whirlwind, an adventure, and we have dedicated ourselves completely to advancing our knowledge of and commitment to Judaism.

My wife went on to study Jewish Communal Social Work as a Federation Executive Recruitment Education scholar at Yeshiva University and Jewish thought at Neve Yerushalayim Seminary, and I returned to pursue simultaneous graduate study in Jewish history at various Universities and Talmudic training at several campuses of Yeshivat Ohr Somayach. Chasing Jewish education, we moved ten times in the first seven years of our marriage (four countries on three continents). Somehow we managed to keep it all together while raising six kids.

Over the course of teaching Jewish history to adult students for the last thirty years I have accumulated many formative experiences. Given the restrictions of space, however, I will share only one.

In 1991 I returned to Ukraine to conduct archival research for my dissertation in Jewish history. It was my second trip there—on the first, two years earlier, I was summarily denied access to the secret Communist Party archives. With the spirit of glasnost’ that accompanied the fall of the Soviet Union, my Ukrainian colleagues hastily arranged for another invitation, correctly fearing that the window of opportunity would shortly close as the country descended into political chaos and potential war with Russia.

When my flight landed in Kiev I learned that my contacts had all fled the unrest in the city. I had a little Canadian cash and plenty of food (my wife packed me a huge trunk of kosher staples) but nowhere to spend the night. As the sun set, and surrounded by suspicious characters representing the resurgent post-Soviet mafia, I heaved the trunk into a taxi and sought out the Antonovsky family. I had met them only once before, when I delivered some insulin on behalf of the Canadian Jewish Federation, but they graciously took me in. I spent several months sleeping on their sofa and later arranged to have my housing stipend directed to them, a financial windfall that came just as the local currency collapsed.

Every night, following our dinner of local fare and imported delicacies from the trunk, we would discuss Jewish history. I learned from them that there was a qualitative difference in terms of how we related to the topic. For me, it was a deeply satisfying intellectual pursuit, meaningful and life-affirming. For the Antonovskys, Jewish history was their very existence. My artless descriptions of Jewish history frequently brought them to bitter tears or shouts of exultation as they learned of events that had long been suppressed by the Soviet regime. In short: Jewish History mattered! My destiny became clear: I decided to spend my life in service to my people as a teacher of Jewish history.

Statement of Purpose

We have all heard the directive issued by the Federal Aviation Administration: in the case of cabin depressurization, passengers must put on their own oxygen masks before attempting to help others. This truism, however counterintuitive, is obvious to anyone who flies with children: we are no help to our kids if we pass out from oxygen deprivation before they get their masks on.

Maimonides offers an identical teaching in the context of Jewish education. He writes, “if a person is to learn Torah, and has a child who is to learn Torah—the parent comes before the child.” We are no help to our children, the next link in the chain of Jewish civilization, if we don’t take care of our own Jewish education first. Yet how may we achieve this essential goal, when the oxygen is rushing out of the fuselage and the plane is careening toward the ocean?

In 2008 I was introduced to the thought of Clay Shirky, a professor at New York University who specializes in the social implications of the Internet. He challenged me to rethink what I had been doing with Adult Jewish Education—and come up with something optimized for millennial and post-millennial Jews. Around the same time I read Rabbi Jonathan Sacks’ A Letter in the Scroll (2004) and was deeply moved by this passage:

Imagine that, while browsing in the library, you come across one book unlike the rest, which catches your eye because on its spine is written the name of your family. Intrigued, you open it and see many pages written by different hands in many languages. You start reading it, and gradually you begin to understand what it is. It is the story each generation of your ancestors has told for the sake of the next, so that everyone born into this family can learn where they came from, what happened to them, what they lived for and why. As you turn the pages, you reach the last, which carries no entry but a heading. It bears your name.

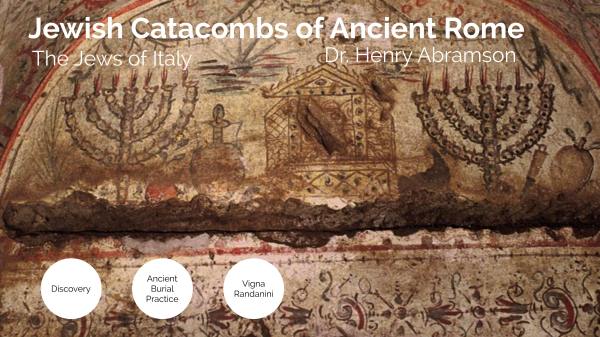

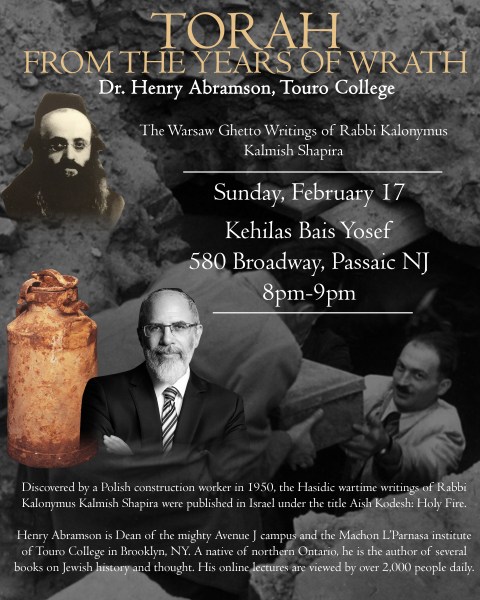

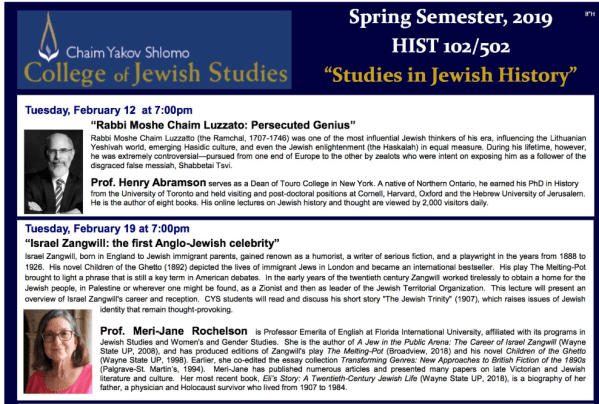

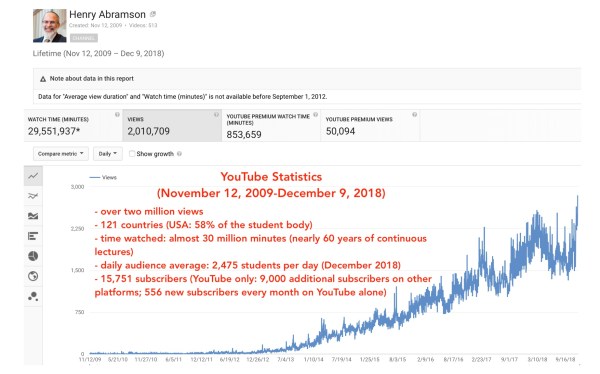

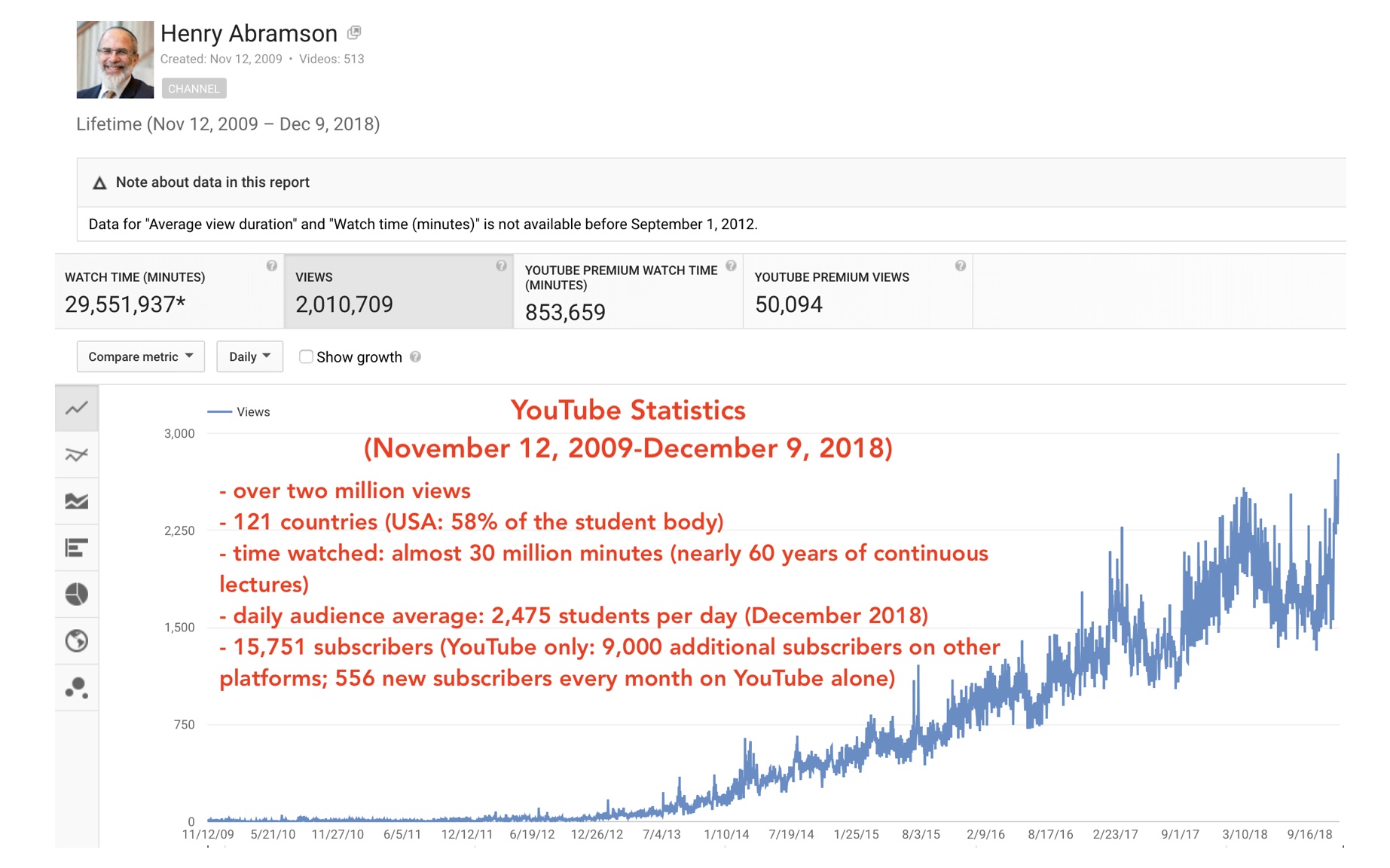

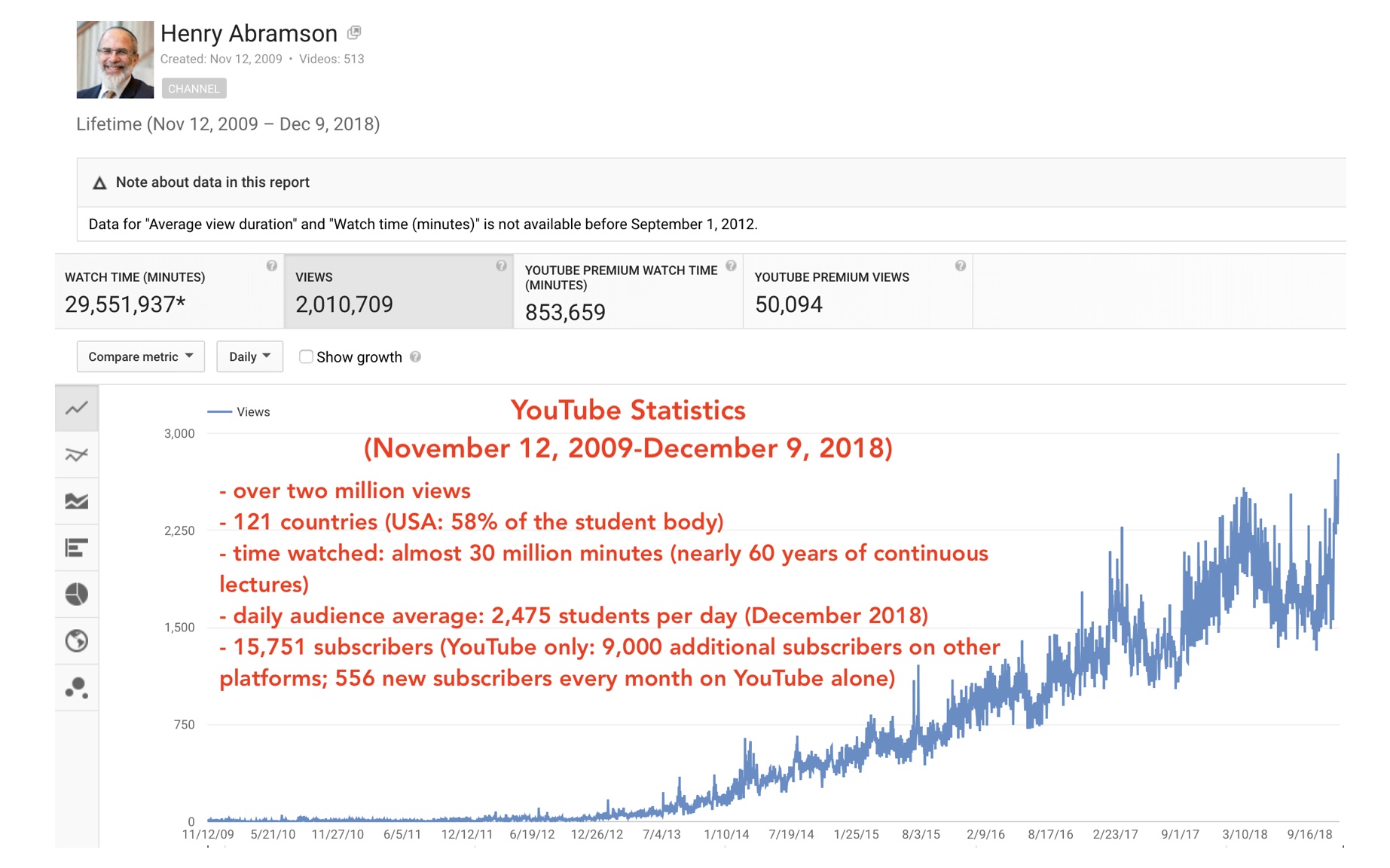

I resolved to take my passion for Jewish history and build an online classroom optimized for digital natives (i.e. anyone born after 1985). The idea was to create a living library in the mobile phone of every Jew world-wide, where one could wander the stacks and discover the volumes with their own names on the spines. I began experimenting by uploading my weekly classes at a local synagogue to YouTube—to my surprise and delight, the lectures rapidly found a wide and diverse audience. Over 500 lectures later, and using several social media platforms, I am still amazed by the statistics. Here’s an annotated screenshot, for example, of the YouTube analytics:

I made a lot of mistakes, especially at first. The medium of teaching online is radically different than teaching in-person—it’s not enough to simply tape a lecture and throw it online. Students learn from the whole environment—punctuations of a chuckle or a yawn from the back of the room, physical movement as the instructor walks from side to side, variations in volume and pitch and the like are impossible to capture on a two-dimensional screen. Students in a classroom expect a few moments of good and welfare announcements to get ready for the lecture, students online expect it to begin immediately. All these lessons had to be learned (and many more that I am still working on). Nevertheless, the statistics suggest that the improvements are taking effect.

Like anything, Jewish history can be poorly taught, and the advantages described above may be squandered by an insensitive or ill-informed instructor. I try to base my own teaching on a credo, outlined in a video Manifesto I developed early on in this process.

We believe:

– The study of Jewish history has meaning and value for human existence in general, for both Jews and non-Jews

– Academic Jewish history lectures need not sacrifice content to be entertaining

– Access to high-quality information on Jewish history should be free

– Shared intellectual curiosity about Jewish history is a great way to build communities

– Jewish history of one of many paths to the study of Torah, and that Torah study is enhanced by a fuller understanding of Jewish history

The project is still in medias res as I experiment with other modalities of online education, but I am pleased that so many other people have joined me in this global conversation about Jewish history. I take special pleasure, however, when I get an email from a middle-school teacher who says she used my lectures to prepare her classes, or from the adult education coordinator of a temple who organizes a weekly watch party for her congregants. That’s when I know that everyone has their oxygen masks properly in place.

Should my application be accepted, this prestigious award would allow me to improve the technical quality of the lectures, for example by hiring students to operate a second camera and edit the final product, giving online viewers a richer experience of the lectures. I’d also like to develop a stand-alone app that directs students to further resources. I’d also like to experiment with ways to bring more online viewers into bricks-and-mortar settings, perhaps by teleconferencing into classrooms into Jewish schools or congregations, or developing printed materials for study groups.

I am grateful to the consideration of the Awards Committee as you reviewing my materials. Knowing that the Covenant Foundation cares about what we do is a huge encouragement to all of us.