A mysterious figure of the early 18th century whose work, recently discovered by Dr. Yohanan Petrovsky-Stern, sheds light on the world of popular culture from which Hasidism emerged.

Click here for the Prezi associated with this lecture.

This article originally appeared in the Five Towns Jewish Times on March 3, 2016.

By Dr. Henry Abramson

Working in the abandoned Judaica collection of the Kiev Vernadsky Library during the immediate post-Soviet period, a brilliant young Jewish historian named Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern discovered a rare 300-year-old manuscript. Ignored by Communist scholars for a century, the well-thumbed, 760-page manuscript, bound in leather with a wooden cover and copper breastplate, was not catalogued in any of the collections of the library. Its unusual Ashkenazic script and numerous drawings of complex Kabbalistic symbols fascinated Petrovsky-Shtern, who was on a personal journey to rediscover his ancestral faith. What was this mysterious, one-of-a-kind book?

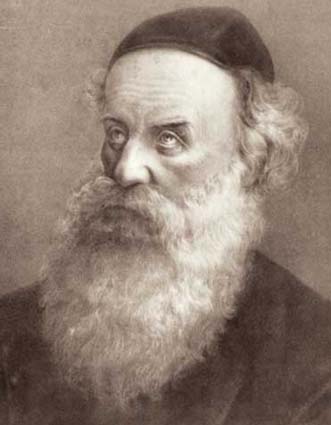

After nine years of extensive research that took him to archives around the world, Dr. Petrovsky-Shtern published the answer. Sefer HaCheshek was a rare, secret guide to practical Kabbalah, written when Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, the founder of the Chassidic movement, was just beginning to deliver his revolutionary teachings. The author’s name itself sheds light on the significance of the text. Hillel styled himself as a Ba’al Shem, literally Master of the Name [of G‑d], a term used to describe itinerant amulet-makers who typically sold their services to simple Jews seeking Kabbalistic remedies for their problems. Shaman-like, these frequently unlearned and often unscrupulous individuals traveled from shtetl to shtetl, performing exorcisms, treating various ailments, and writing amulets for a wide variety of purposes: health, prosperity, marriage, children. Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, by contrast, was known as the Ba’al Shem Tov, the “Good” Master of the Name, because his work was of an entirely different order.

The Sefer HaCheshek contains both extensive instruction in Kabbalistic healing and a surprising degree of autobiographical information. Dr. Petrovsky-Shtern, now a distinguished historian at Northwestern University in Chicago, argues convincingly that the manuscript was written as a type of curriculum vitae, as Hillel wished to end his peripatetic existence and secure a permanent position, preferably in Germany. Sefer HaCheshek was intended as a demonstration of his experience and expertise, having apprenticed to both medical doctors and reputable Kabbalists. Whether or not he received the position—an honor that was bestowed on his contemporary, the Ba’al Shem Tov, in the Ukrainian town of Medzhybizh—is unknown. Nevertheless, Hillel Ba’al Shem’s description of his prior experiences (especially a dramatic exorcism in Ostrah) illustrates the state of popular religious practice in pre-Beshtian Eastern Europe, and provides a vivid backdrop for the emergence of Chassidism.

Why did Chassidism flourish, and the populist, theurgic Kabbalah of Hillel and other ba’aleiShem decline? Dr. Petrovsky-Shtern provides a salient analysis by identifying what was absent in Sefer HaCheshek. Despite its encyclopedic coverage of remedies for every possible physical, psychological, romantic, and economic malady, Hillel Ba’al Shem delivers no message of universal human redemption. Unlike the Ba’al Shem Tov, whose teachings emphasized human potential and the value of community, Hillel relies on magical one-time fixes, not personal spiritual growth. To the crestfallen he offers no counsel; to the bereft, no benefit. The terminology employed in his work is similar—Hillel refers to Kabbalistic disciples as chassidim, for example—but the contrast between the numerous but forgotten Ba’alei Shem and the magnificent Chassidic world founded by the Ba’al Shem Tov could not be more profound.